Nothing is There

Written by Anna Karpenko, the text was commissioned and originally published by Dwutygodnik magazine as part of the project "Amplifier of Shout - Belarusian Art in Times of Protest", financed by the Foundation for Polish-German Cooperation with funds from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Federal Republic of Germany. Partners of the project are the Goethe Institut and the Belarusian House Foundation in Warsaw.

In 1998, Belarusian philosopher Valiancin Akudovič published one of his program texts, "I Don’t Exist. Reflections on the Ruins of Humanity '', which formalizes the intellectual, cultural and existential nature of living in the space called Belarus. In the 2000s, artist Aliaksiej Lunioŭ (Alexey Lunev) creates the frequently quoted now work "Nothing is There", which passes a sentence on the Belarusian space of the early noughties. If for Akudovič the metaphor of absence has something to do with the attempt to overcome the binarity of the national identity modes built on the opposition between East (Russia) and West (Europe), for Aliaksiej Lunioŭ this total emptiness of the Belarusian cultural space, in which it is not only impossible to express oneself, but literally nowhere to do so, is an epitaph on the plate of the local art field.

Marginality and "exclusivity" in the sense of the Belarusian contemporary art being excluded from the visible public context have been associated for decades primarily with the impossibility for contemporary artists to be displayed in state institutions. The only institution in Belarus formally connected with the field of contemporary art, the National Centre for Contemporary Arts, represents a classic hierarchical state organisation subordinate to the Ministry of Culture that actively employs censorship. For example, during the exhibition "Everything was Different" (curated by Mikhail Gulin and Taciana Kandracienka), the artwork of Maryna Saboŭskaja (Marina Sobovskaya) was censored and removed from the exhibition in 2006. In 2016, Aliaksiej Talstoŭ (Alexey Tolstov) finds himself in the NCCA storerooms, and after examining the purchase list, wonders who, how and at what cost acquires artworks for the Centre for Contemporary Art collections. The rhetorical question results in a legal battle between the artist and the institution. It turns out that the purchasing is classified and cannot be disclosed or made public, despite the fact that the institution is a state organisation and exists on taxpayers' money. The artist loses the trial to the system.

In 2009, a Gallery of Contemporary Art “Ў” opens in Minsk, scaled up from a small but influential gallery “Podzemka” run by Valiancina Kisialiova (Valentina Kiseleva) and Hanna Čystasierdava (Anna Chistoserdova). For more than 12 years, the gallery has been one of the main institutions for contemporary art in Belarus. In the summer of 2020, one of its founders, businessman and philanthropist Aliaksandr Vasilievič was detained as he and a dozen others line up in front of the KGB building to stand surety for Viktar Babaryka (detained and later convicted to 14 years in a colony with a reinforced regime; one of the presidential candidates in the 2020 elections). A month and a half later, Aliaksandr Vasilievič was detained again and placed in the KGB pre-trial detention centre, where he has been awaiting trial for over a year (i.e. he has not yet been charged). In November 2020, the gallery “Ў” in Minsk closes down. Its art directors are leaving Belarus for security reasons.

On 30 June 2021, Belarusian authorities compel the Goethe Institute in Minsk and the DAAD: German Academic Exchange Service to shut down their activities in Belarus within two weeks[1]..Since 1993, Germany's cultural Goethe Institute in Minsk has been one of the few Western European cultural organisations with an official representative office in Belarus that has been actively involved in the formation and development of the local art scene.

During the collapse of the USSR, when the first Western cultural projects of perestroika were introduced in the former Soviet Union, Belarus remained the only country where the Soros Foundation, known for its cultural projects, including in the field of contemporary art, did not open its Centre for Contemporary Art. In Ukraine, for example, there were two such centres, in Kyiv and Odessa. Why was it important? Because during the transformation of the Soviet system, the Soros Centers for Contemporary Art in the post-Soviet countries, given all the ambiguity of their agenda, were often the only window and bridge between the local art scene and the global world. Certainly, they can be considered a typical colonial project that used art as a political instrument, but the very physical existence of such a centre as an institution provided a basis for the development of contemporary art structures in many post-Soviet countries.

This was not the case in Belarus. The same was with the representative offices of major international institutions such as the British Council or Pro Helvetia, and many others. The few projects that these institutions supported in Belarus were part of the projects of their Russian initiatives. This once again reinforced the institutional and intellectual burden we have been trying to free ourselves from for the last 30 years – positioning Belarus as part of the Russian cultural region.

The Goethe Institute in Minsk was one of the few European institutions that viewed Belarus as an independent space. And this provided an opportunity to fill the voids of the late nineties and early noughties. This included a policy of distancing ourselves from the regional division into cultural entities based on the political proximity of the regimes in Belarus and Russia.

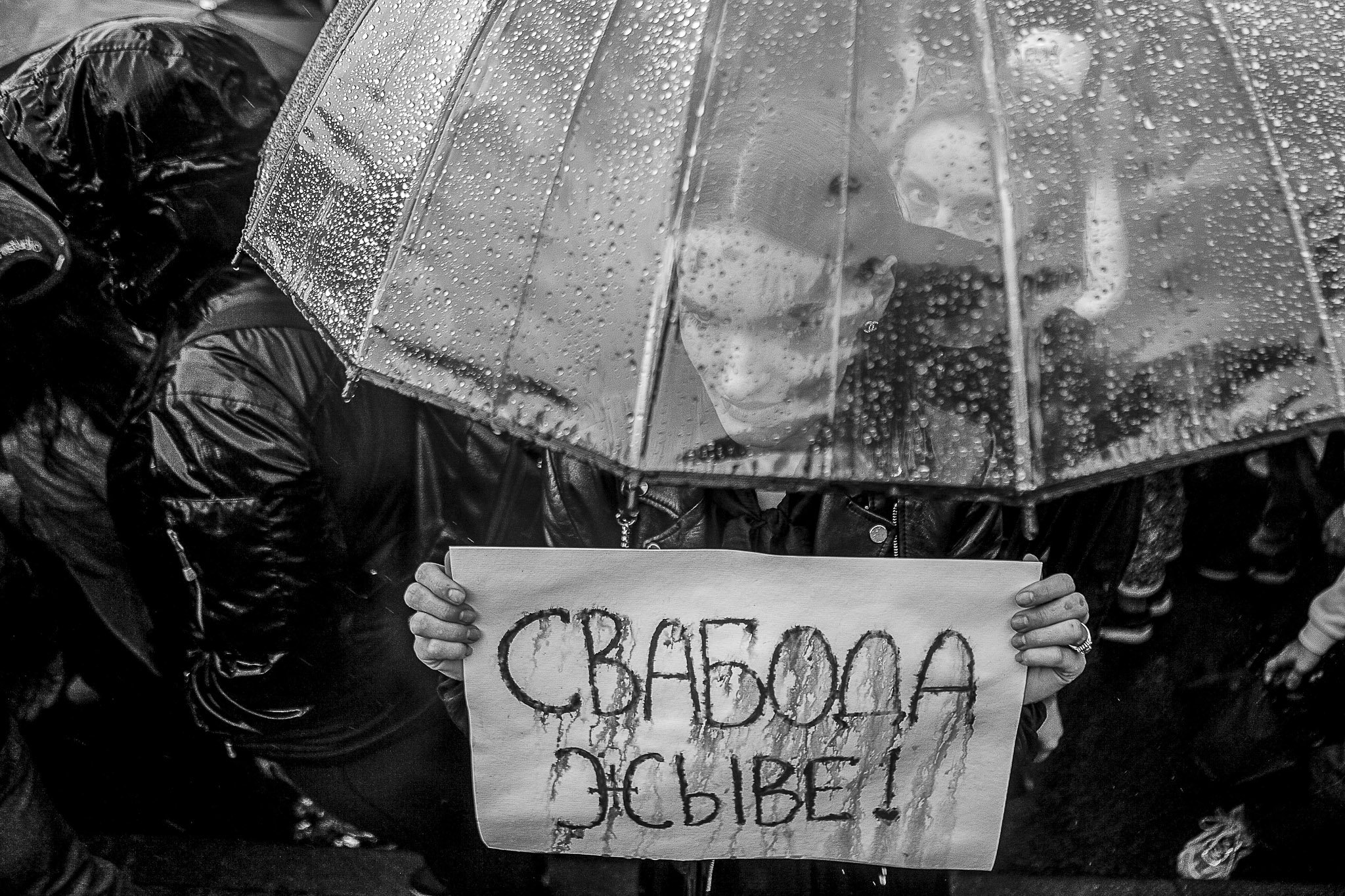

After the brutal crackdown on the most massive peaceful protests in the history of Belarus against once again rigged presidential elections, when Lukashenka seized power for the sixth time, the Belarusian cultural space has experienced another existential death and a new round of the dialectic of emptiness. There are neither institutions of art, nor its actors in Belarus now. There are no more people who can preserve and develop this field. Over the past year, according to unofficial estimates, some 40,000 people have left the country. Not all of them worked in the field of culture, but most are an active, well-educated part of the society, who have braved forced political and economic migration to Ukraine, Lithuania, Poland, Germany. More than 4,000 people are under arrest for political reasons or recognized as political prisoners. Among them are artists (Ales Pushkin), musicians, students of the Belarusian Academy of Arts and other colleges, writers, businessmen, lawyers and journalists.

Some of the cultural workers forced to leave Belarus have moved their projects to a new place of residence. Gallery “Ў” plans its activities in Poland and Germany, Andrei Liankevich, director of the only Belarusian Photography Month in Minsk is running a festival in Poland. Expelled from its own premises, the oldest Belarusian theatre "Kupalaŭski" partly moved to Warsaw and switched to the virtual space, becoming a youtube theatre. We seem to still be there, but in our own space we 'don't exist'.

The archaic cyclicality in which you find yourself in Belarus turns out to be a succession of alternating events in perpetual repetition; it seems as if everything has already happened and it is impossible to cut the noose of time around your neck.

In 2010, there was yet another so-called election. There was another "Plošča" (the peaceful protests on the square in front of the Government House), which was brutally dispersed by internal troops and OMON (riot police). There were mass arrests of all presidential candidates; criminal cases against NGOs, human rights defenders, activists, independent cultural organisations; bargaining with the European Union to get rid of sanctions in return for the release of political prisoners. In 2020, it all happened again with renewed vigour.

In 2011, Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius and then Zachęta National Gallery of Art in Warsaw hosted an exhibition "Opening the Doors? Belarusian Art Today.” The question raised by the project curator Kęstutis Kūzinos – whether the doors to that space called "Belarusian contemporary art", unknown even to the neighbouring countries Lithuania and Poland, are really opening – has not lost its relevance. Then, in 2011, it was actually the first large-scale group exhibition of contemporary Belarusian art in Vilnius. The city is only 170 km away from Minsk, but there is such a huge wall between Lithuania's aspirations towards Western world, and the total deafness of official Minsk to any kind of contact with European countries. Most of the artworks displayed at "Opening the Doors? Belarusian Art Today" could not have been shown in Belarus then or now in any of the official art institutions, due to the political context of the works on the one hand, and the censorship of the institutions on the other. More than half of the participants in that exhibition had no longer lived in Belarus at that time, having fled to European countries as they couldn’t realize their professional potential in their home land.

Exactly 10 years later, Kyiv's Mystetskyi Arsenal is hosting a major exhibition dedicated to the art of the Belarusian protest movement "Kožny dzeń (Every Day)" (curated by Aliaksiej Barysionak, Marina Naprushkina, Antanina Stebur, Sergey Shabohin, Andrej Durejka and Maxim Tyminko), featuring artworks by 90 artists from Belarus, some of whom were forced out of the country during the repressions of 2020–2021.

When we talk about contemporary Belarusian art and its form of existence over the past two years, we have to keep asking ourselves: are we still there or are we already gone? And if we are still there, where are we exactly? Where do we belong? One of the popular and frequently used slogans during the 2020 peace marches was "This is our city![1]" And this was not just an attempt to reclaim the public space that had not belonged to the Belarusians since 1994. It was an assertive statement of the unchanging fact of our existence in this place for the authorities. We do actually exist, we are here, and this is our city.

Now, almost all independent initiatives in this city have been closed down or eliminated (Gender Route, Radzislava centre for victims of domestic violence (Olga Gorbunova, its permanent leader, is in jail at the moment); more than 20 journalists are in prison, independent media and cultural spaces have been eliminated). Some are in prison, some have fled, some have stayed and are struggling to survive in the face of the ongoing repressions, insecurity and humanitarian gloom.

In November 2021, I was lucky enough to attend one of the few offline events at the CIMAM-2021 conference, “Under Pressure. Museums in Time of Xenophobia and Climate Emergency”[2]held in Lodz and Gdansk (Poland). Distinguished representatives of European, American institutions and independent curators discussed the problems and tensions that museums face today in a situation of increasing right-wing politics in European countries, and dealing with the consequences of colonial strategies and post-capitalist imbalances in the distribution of natural resources. We were listening to the reports about the protests against the MoMA in New York, looking into the case of the Swiss Kunsthalle where a person of colour joined the team for the first time, discussing the particularities of the adaptation of migrant communities in Germany through museums, while a humanitarian disaster was unfolding 300 km away at the Belarus-Poland border[3].And 600 km away in Minsk, 20 people were sitting in a prison cell designed for 8, without toilet paper, mattresses, parcels, letters and medical care.

This is my institutional reality, my museum Under Pressure in a space that does not exist for New York MoMA publications on Central and Eastern European art[4].

We don't exist. But we are still there.

[1] https://www.dw.com/ru/gjote-institut-i-daad-v-minske-zakryvajut-kak-reagiruet-frg/a-58126779

[2]https://cimam.org/cimam-annual-conference/annual-conference-2021-poland/

[3]https://www.dw.com/en/migrants-stuck-in-political-battle-at-belarusian-polish-border/av-59817543

Anna Karpenko, Independent Curator, GFZK (Leipzig) and CIMAM 2021 grantee.

Through CIMAM's Grant program, 50 contemporary art curators, researchers, and museum professionals from 32 different countries were awarded to attend the CIMAM 2021 Annual Conference, in-person and online. Titled Under Pressure. Museums in Times of Xenophobia and Climate Emergency, the conference was held in Lodz and Gdansk, Poland 5–7 November 2021 hosted by Muzeum Sztuki in Lodz and the NOMUS New Art Museum/ Branch of the National Museum in Gdansk.

Grants were generously supported by the Getty Foundation, V-A-C Foundation, Byucksan Foundation, Mercedes Vilardell, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, and the Office for Contemporary Art Norway.

CIMAM’sGr ant Program supports individuals’ curatorial and research development through their attendance at the Annual Conference where the most current concerns on contemporary art practices are being d