What Good Is Eco-Art Without Community?

Originally written by Alicia Grullón. Published by Hyperallergic, August 22, 2023.

From outlandish and self-aggrandizing Land Art projects of the 1970s and ’80s to newer projects involving community gardens, stewardship, and holistic practices, the tension between who is involved in ecologically themed art projects and how and why they are activated remains unresolved. The question that is asked by some working-class communities in New York City regarding participatory art projects and the environment is, “Okay, but what about the people?”

While attending Creative Time’s Parallel Walks series, I engaged with many questions about art projects and ecology. Part of Creative Time’s new initiative, Creative Time HQ — “a forthcoming gathering space for art and politics” — the idea behind this series is to highlight “artist-led walks that take place in two locations connected through a shared political, social, contextual, or geographic theme.” As a lifelong New York City resident experiencing the overwhelming changes brought on by gentrification and significant demographic shifts, I wondered why capitalism’s impact on the environment is consistently underplayed. In neighborhoods where longtime residents are being displaced by landlords and city government officials who would prefer wealthier residents, how can environmentally oriented art projects not consider the experiences faced by New Yorkers in areas under constant police surveillance and in critically underserved places? By “underserved,” I mean neighborhoods that appear to be lacking Department of Sanitation oversight to clean trash from streets and provide sufficient garbage cans; areas where residents are part of the 4 million+ without medicare; and neighborhoods where chronically misguided AMI “affordable” housing development is not meant for those who are being displaced.

The first walk, “Creating a Community Forest,” took place on August 12 in the Northwest Bronx, along Mosholu Parkway, an area stretching about three miles surrounded by parkland on either side. Built by Robert Moses during the depression, it was a continuation of a greenbelt connecting the northwest Bronx to other parkways along the Bronx River in the south. At the time that Moses began construction, the area’s demographics were largely upper-middle-class Jewish and middle-class Irish. By the 1980s, largely due to “white flight,” city agency services declined, leaving the area dilapidated.

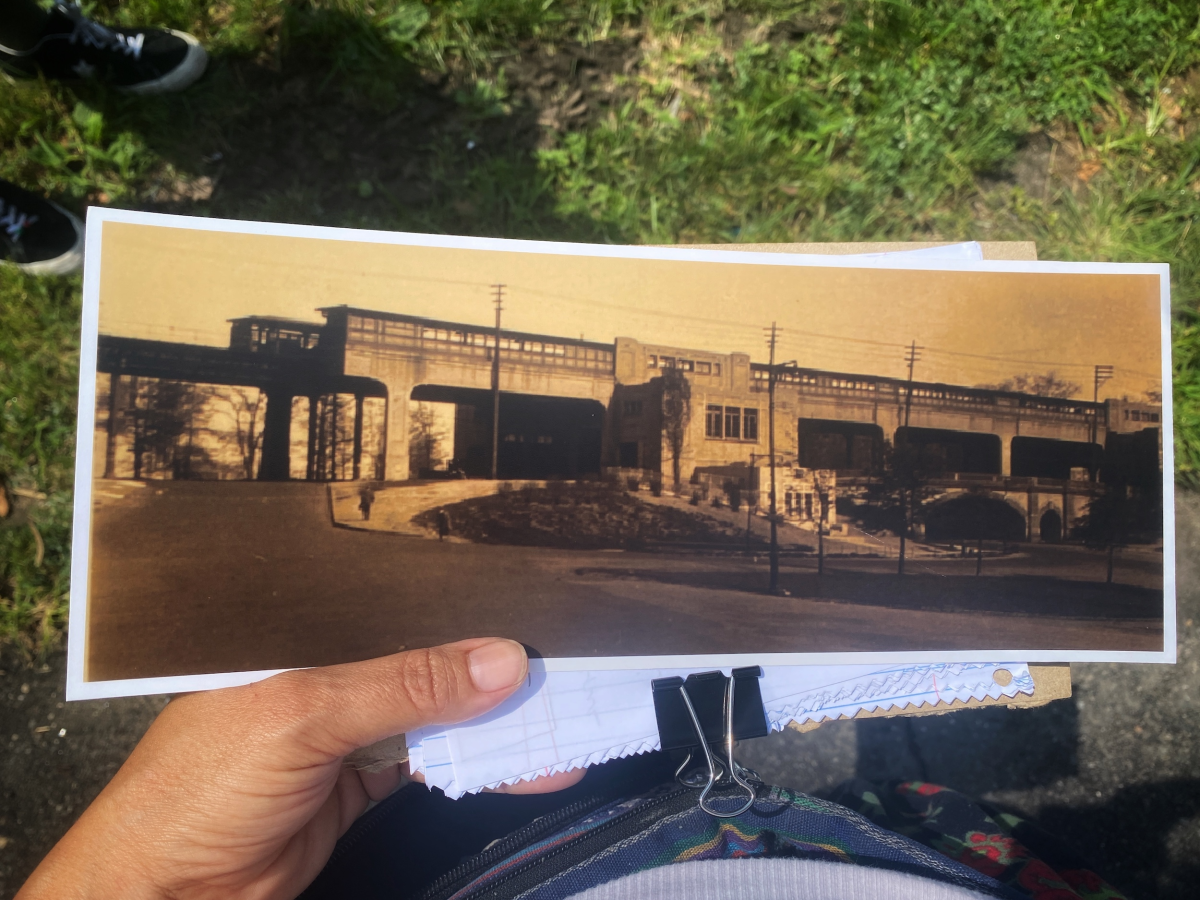

Artist Matthew Lopez-Jensen, who led the walk, started with a gentle clean-up and brief land acknowledgement. Shortly after, he shared his aspirations to rehabilitate a comfort station within the #4 subway station at Mosholu Parkway which has been closed down for decades, to facilitate parkland stewardship. It was at this time that three local community members spoke out against the walk, its non-community participants, and the use of “neglected” to describe the area. Olga Segura, whose newsletter Bronx Frontlines covers identity and displacement in NYC, pointed out the absence of local community members, and noted that community members were actively restoring the neighborhood, but were consistently shut down by the NYC Parks Department and the Department of Transportation (DOT). Another community member, Siddika Dejia, a former Montefiore Hospital employee, shared how current residents, primarily Black and Brown immigrants, are facing an unprecedented chokehold by landlords and Montefiore Hospital attempting to price them out of their apartments to accommodate medical students. Rainey Cruz expressed their disappointment in the eco-art projects they’ve encountered, saying, “the focus on trash and pick-up itself always feels reductive because it’s an easy way to frame ‘neglect’ without any upstream accountability to deeper-rooted issues of food, housing, health, and resources in the community. Anyone can continuously come and clean, take pictures with politicians and organizations, but really no change is happening.”

The second walk took place on August 17 on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. “Foraging in the city! What is it? How is it done? And is it worth it?” was led by Journei Bimwala. The group started outside 20 Cooper Square, one of many buildings New York University owns in its “14 million square feet of land across about 110 buildings.” NYU, one of the largest landholders in New York City, has transformed Greenwich Village, “contributing to gentrification, or the influx of wealthier residents — students, in this case — into an established urban neighborhood.” A current artist-in-residence at the Bronx River Alliance, Bimwala began by pointing out plants and weeds in a small triangular green space on Cooper Square owned by the DOT. The walk ended with an in-depth look at making oxymel with medicinal plants Bimwala brought from Concrete Park in the Bronx. Toward the end of her workshop, she explained that at the close of their cycles, plants will put their energy back into the ground to start anew. At this point, I had an overwhelming sense of grief regarding where I was and what kind of energy was being put back into the ground. Having grown up in New York City, the East Village has become unrecognizable to me. It’s where small triangular green spaces function as consolation prizes for billion-dollar developments. Is this what my neighborhood in the Bronx will eventually look like?

The intention of Parallel Walks’ organizers and artists to do better in the world through their skills and positions and to promote the benefits of caring for nature and ecological struggles in NYC was evident. And yet, I also saw a discernible trend in refraining from assuming an active position against the backdrop of prevailing political and economic forces.

People ranging from Indigenous writers to social ecologists point to the fact that humans cannot be separated from the environment. Our lives and experiences psychically and physically create the ecology. Ensuring the full participation of individuals within the community is ensuring that in 20 years’ time, those who want to remain in a community have the support that allows them to stay. Obscuring or neglecting the connections between people, capitalism, and the environment obliterates the honor and hardships of those who are diminished alongside nature. Unfortunately, in most eco-art initiatives and activist projects the experiences of the people are seldom as idealized as the eco-projects meant to safeguard the natural world.