The Rise of “Immersive” Art

Written by Anna Wiener, originally published by The New Yorker, February 10, 2022.

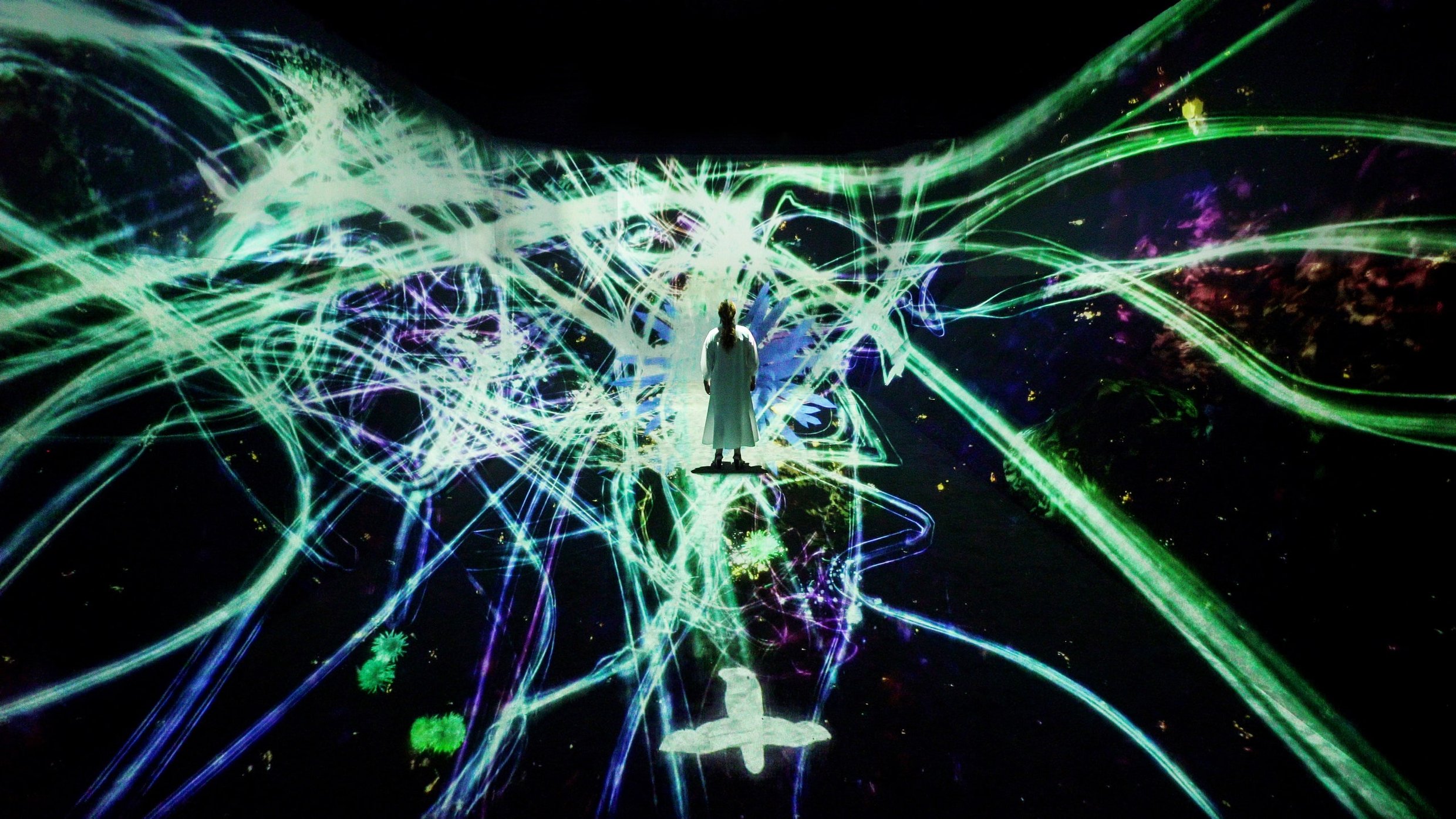

The lights were off, the air smelled faintly of roses, and New Age music flowed from room to room. TeamLab, a Japanese art collective of six hundred “ultratechnologists”—artists, software engineers, animators, and architects—had taken over an eighty-five-hundred-square-foot gallery at San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum. Their “interactive landscape,” called “teamLab: Continuity,” promised “a wondrous ecosystem of lush imagery drawn from nature and East Asian art.” Animated projections of flowers, fish, and birds drifted across the walls and floor; as visitors moved, the images reacted, creating ephemeral, mutating patterns. Butterflies, when “touched,” faded and crumpled; blossoms and pine needles changed colors, or were swept aside. A woman tried to dodge a school of fish, which pooled and scattered around her boots. Looking around, I figured that the room was stuffed with sensors. (TeamLab is evasive about its technology.) “My hand just went through a tadpole,” a girl behind me said.

“Continuity” is one of many technology-driven “immersive” installations, which have grown popular in recent years. Operated by artist studios, collectives, and production companies, these projects range in finesse from sophisticated new-media installations to animated retrospectives of Impressionist painters. I entered a room dedicated to a piece titled “Crows Are Chased and the Chasing Crows Are Destined to be Chased As Well, Transcending Space.” Projection-mapped animations soared around me, shifting the center of gravity. Sweeping, cinematic music played, and the room appeared to move. In the catalogue for the show, Karin Oen, a curator at the museum, argues that teamLab’s work invites visitors to “go beyond passively observing,” instead making them “active protagonists in decentered narratives”; Toshiyuki Inoko, teamLab’s founder, has said that the organization aims to obliterate boundaries between the self and the environment. “This is so trippy,” a small child said. “This is extremely trippy,” his tiny brother echoed.

I watched a group of crows beat across the ground, up a wall, and out the door. I followed them into an alcove, where a cluster of adults admired an explosion of sunflowers. In another corner of the room, butterflies pooled on the torso of a woman wearing a black winter jacket. There was something a little transactional about the interactivity; its action-reaction responsiveness reminded me of the mirror game, or contact improv. People took pictures of themselves and of one another. I took a few of my own and, cupping a hand over my phone to dim its light, texted them to a friend. The images looked somehow more arresting and otherworldly on a small screen—more consistent with the elevated rhetoric of the show. In person, the projections were legibly one-dimensional, but in photographs the gallery’s mirrored walls gave the impression of endless depth.

Later that afternoon, my friend called. He had seen the photos, and found them deeply strange. “There’s something interesting about something so maximal falling so short,” he said. “The thing that’s truly immersive is your phone.”

In 2020, the Serpentine Galleries, in London, released a report titled “Future Art Ecosystems.” It surveyed emerging practices among artists who work with “advanced technologies”: everything from gene-editing to blockchains. The report, which was co-produced by a consultancy and framed as a strategic document, identified the trend of tech companies acting as art patrons, and advanced the idea of the “art stack”—a vertically integrated, artist-led system of production that operates at “unprecedented scale,” bypassing the art establishment through centralization. In software engineering, a “tech stack” usually refers to a system’s foundational software components, and a “full-stack” engineer is fluent in both front-end and back-end development. A full-stack art studio would own the process from beginning to end, employing both artistic and technology teams and controlling its own revenue streams and gallery spaces. Like movie studios, record labels, fashion houses, and video-game companies, studios that mastered the art stack could someday adopt an “industrialized” model, the report suggested; to monetize their offerings, they could broker corporate sponsorships, partner with real-estate developers, offer nonartistic technical services, or operate “like circuses and theme parks,” going direct-to-consumer with mass-market, ticketed experiences. There could be art-stack I.P.O.s.

A number of organizations and artists already operate in this mode, more or less. They include Studio Drift, which recently held an “immersive exhibition” of kinetic sculptures at the Shed, in Hudson Yards; Random International, whose 2012 “Rain Room” was a global crowd-pleaser; and Refik Anadol Studio, which creates, among other things, “parametric data sculptures”—abstract data visualizations, displayed on massive L.E.D. screens. No artists’ collective seems to embody the art-stack model as fully as teamLab. Since 2018, in partnership with Mori Building, a major Japanese real-estate developer, the group has operated teamLab Borderless, an enormous exhibition space in Tokyo. Early press releases touted Borderless as an “unprecedented digital art museum,” and highlighted its hundreds of computers and laser projectors. The facility’s fifty exhibits include “Black Waves: Continuous,” in which illustrated swells tumble and crash hypnotically around visitors, who are encouraged to lie back and relax, and “Forest of Resonating Lamps,” a mirrored room hung with hundreds of Murano glass pendants that react to movement. In its first year, Borderless attracted more than two million visitors, who paid about thirty dollars per ticket.

In 2019, teamLab, which uses Epson projectors, opened a Borderless museum in Shanghai, sponsored by Epson, and signed an eleven-year lease on a large gallery space in Brooklyn’s Industry City development. The Industry City plan fell through, but in 2020 teamLab opened SuperNature, a “body immersive” art space inside the Venetian, a luxury hotel in Macau. The group is represented by Pace, the blue-chip art gallery. The same year, Pace launched Superblue, a satellite company focussed on building “experiential art centers,” or E.A.C.s. (Pace’s partners in the venture are Emerson Collective, the for-profit philanthropic organization founded by Laurene Powell Jobs, and Therme Art, a culturally oriented offshoot of the high-end wellness-and-hospitality group.) The first Superblue E.A.C., a fifty-thousand square-foot converted warehouse in Miami, contains five immersive experiences, including “Forest of Us,” a maze of mirrored and illuminated walls, by the artist and stage designer Es Devlin; “Ganzfeld,” a violet light installation by James Turrell; and a reactive digital environment by teamLab. The works themselves are difficult to sell to collectors or institutions, but Superblue makes money by selling tickets to visitors, with proceeds split between the gallery and the artists.

In many ways, the entrepreneurial bent of the art-stack model dovetails with long-running trends in the art world. It arrives at a time when museums have grown more corporate, and also face pressure to diversify their collections and expand their audiences. Art works are seen as financial assets, and flashy, “starchitect”-designed museum buildings, with airy, open gallery spaces, demand work of a certain size and scale. There is also the long-standing popularity of experiential, environmental art. Artists such as Turrell, Robert Irwin, and Robert Morris began creating such art in the nineteen-sixties and seventies; by the nineties, it had become an institutional fixture. Writing at the beginning of that decade, Rosalind Krauss, a critic and former associate editor of Artforum, argued that such art had altered the nature of museums. Once spaces full of objects, carefully arranged to tell a story, these institutions now sought to “forego history in the name of a kind of intensity of experience.”

The new immersive art also reflects the rise of consumer digital technologies, and the behaviors and expectations that they cultivate. In “Contemporary Art and the Digitization of Everyday Life,” published in 2020, Janet Kraynak, an art historian and professor at Columbia University, argues that the museum, “rather than being replaced by the internet, increasingly is being reconfigured after it.” Museums now treat visitors as if they are the “users” of a consumer product, and thus cater to their preferences, creating “pleasurable, nonconfrontational” environments, and emphasizing interactivity. She suggests that, instead of striving to be places of pedagogy, museums are growing “indistinguishable from any number of cultural sites and experiences, as all become vehicles for the delivery of ‘content.’ ” Kraynak told me that she thinks the user-friendliness of museums is making them less challenging and interesting. “That friendliness is kind of pernicious,” she said. “They’re not equipping the beholder to go outside of oneself, outside of one’s comfort zone.” In this fashion, she went on, museums have assumed a therapeutic function.

Marc Glimcher, the President and C.E.O. of Pace, seemed to regard therapy as part of immersive art’s appeal. “We don’t see a sunrise anymore, we don’t see a sunset anymore,” he told me. “We evolved over millions of years in this incredible environment, and then, over the last hundred, two hundred years, we’ve closed ourselves in, into these cities that erase nature.” People are “hungry for transcendence,” Glimcher said; “churches are emptying,” and “these artists are trying to fill that gap.” Technology, he went on, has facilitated a movement toward “pop art,” which prioritizes the audience over the intelligentsia and seeks to skirt the entrenched art establishment. (He described N.F.T.s as similarly representative of this turn.) As a powerful member of the establishment himself, Glimcher seemed ambivalent about how to frame this development. “When you say we’re bringing transcendent experiences to millions of people, your heart soars,” he said. “When you say this is a populist shift, your heart sinks. The democratization of art sounds great. ‘Populist spectacle’ ”—he let out a groan—“doesn’t feel so good.”

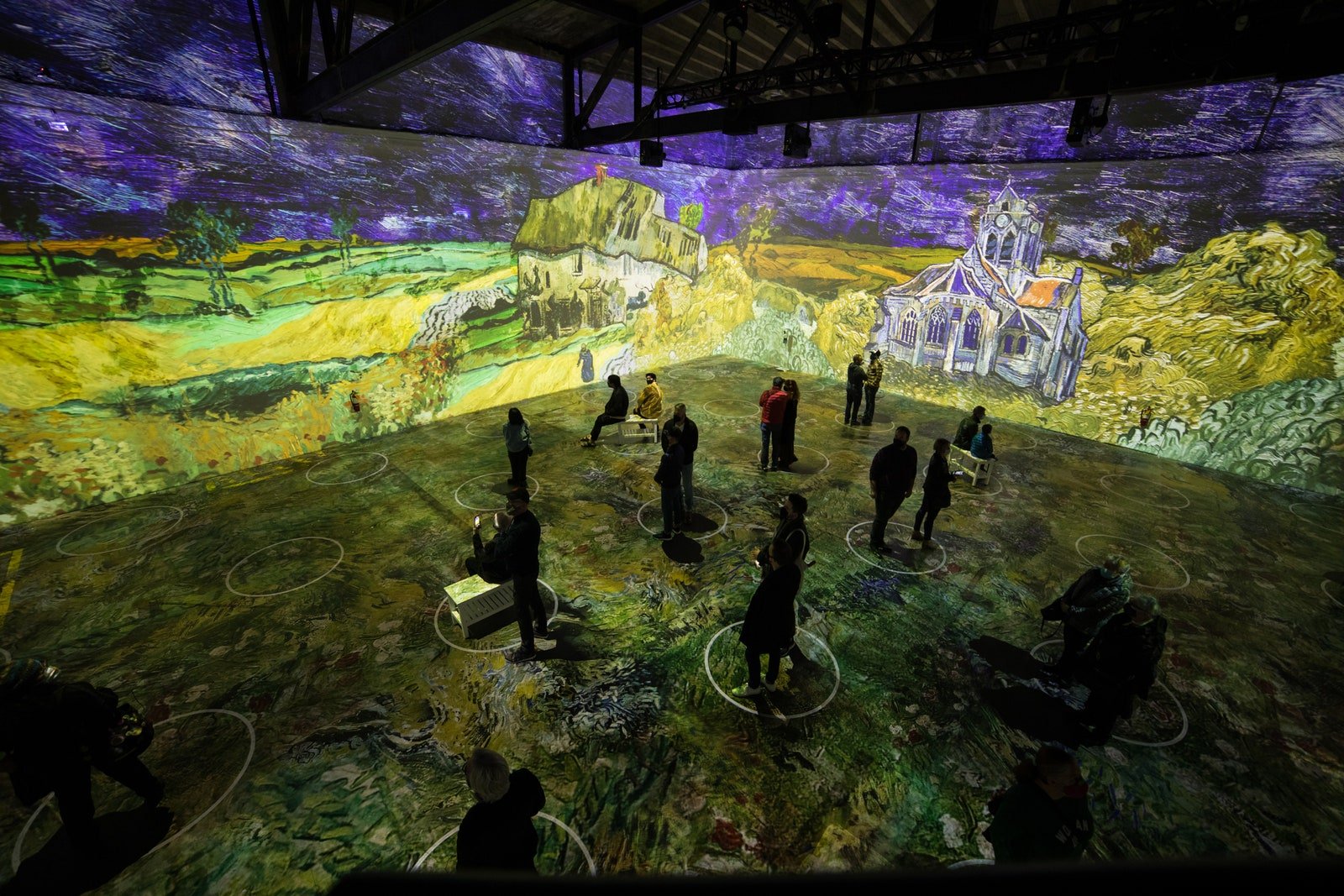

In 2021, Serpentine released a second “Future Art Ecosystems” report, in which the galleries expanded the art-stack category to include both Superblue and “Van Gogh: the Immersive Experience.” The latter isn’t a prestige new-media experiment but a large-format art-historical projection show—one of many exhibits that claim to re-present the work of long-dead artists in a rapturous technological context. Similar shows include “Frida: Immersive Dream” (“Immerse yourself in the art and life of Frida!”), “Immersive Klimt Revolution” (“Step inside his electrifying world and be swept away!”), and “Imagine Picasso: The Immersive Exhibition” (“Literally step into the world and works of the master of modern art”). There is “Beyond Monet” (“Become one with his paintings”) and “Monet by the Water” (“Wander free in a world shaped by Claude Monet’s art”), as well as “Gaudí: the Architect of the Imaginary,” “Chagall: Midsummer Night’s Dreams,” and “Dalí: The Endless Enigma”; the latter is synched to back-to-back albums by Pink Floyd. Most of these exhibitions travel the world, showing in cities across Europe, Asia, and North America. Many are mounted in empty or transitional commercial spaces, as stopgaps of sorts, until a new tenant arrives. Cities, these days, are rich with empty box stores, event spaces, and theatres.

At least in the United States, the sudden proliferation of these shows has been attributed to “Emily in Paris,” a Netflix series about a young, daffy American marketing professional with a frightening wardrobe and a penchant for pageantry. In the show’s first season, which aired in late 2020, the protagonist visits “Van Gogh, Starry Night,” an immersive experience at L’Atelier des Lumières, a real-life “digital arts center” in Paris. “Van Gogh, Starry Night” was not the first immersive Vincent van Gogh exhibit—the form dates back to at least 2008—but suddenly it seemed that walls across North America were being blasted with projections of flattened impasto. At present, there are at least five distinct digital exhibitions showcasing van Gogh’s work, stationed in cities across the world: “Van Gogh Alive,” “Immersive Van Gogh,” “Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience,” “Beyond Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience,” and “Imagine Van Gogh: The Immersive Exhibition.” (The nomenclature brings to mind an Amazon search result.)

We live, supposedly, in the age of “experiences”; the term evokes the tired trope that millennials—the most indebted generation in history—value travel and ephemeral encounters over material goods. In a 2018 Times article titled “The Existential Void of the Pop-Up ‘Experience,’ ” the cultural critic Amanda Hess toured a range of temporary, ticketed experiences in New York City—the Rosé Mansion, Candytopia, the Color Factory, the Museum of Ice Cream’s Pint Shop—and concluded that the real experience on offer was posting to social media. Twenty years earlier, in an article for the Harvard Business Review titled “Welcome to the Experience Economy,” the business scholars B. Joseph Pine II and James H. Gilmore proposed that commercial services aim to engage people “on an emotional, physical, intellectual, or even spiritual level.” There is something very literal about coupling this business philosophy with some of the most famous paintings in the world: visitors are predisposed to awe.

Today, commercial immersive experiences are beginning to move into more traditional, institutional settings. This spring, the Grand Palais, in Paris, will partner with the Louvre to début “La Joconde: Exposition Immersif,” an immersive exhibit based on the Mona Lisa that the organizers say will offer a “unique interactive and sensory experience.” And, in partnership with Grande Experiences, an Australian content-creation company, Newfields—formerly the Indianapolis Museum of Art—has converted a floor of its building into a dedicated exhibition space for immersive digital art, called THE LUME Indianapolis. Marketing materials describe THE LUME as a “contemporary, next generation, fully immersive digital art gallery” involving a hundred and fifty projectors, a musical score, thematic food-and-beverage options, and “suggestive aromas.” (Grande Experiences works with ScentAir, a plug-in-fragrance manufacturer specializing in “memorable customer experiences.”) A catalogue of presentations can be shown on rotation; the Grande Experiences portfolio includes “Street Art Alive,” “Da Vinci Alive,” “Monet & Friends Alive,” and “Planet Shark.” The inaugural show at Newfields is, unsurprisingly, “Van Gogh Alive,” which débuted a decade ago, at Marina Bay Sands, a casino and resort in Singapore.

“Globally, a lot of museums, institutions, they’re finding their visitation is dropping off,” Rob Kirk, the head of touring experiences at Grande Experiences, told me. “They’re looking at ways to bring audiences back—to reënergize the audience. I would say that, in the next five to ten years, there will be more exposure to these types of experiences within those types of institutions.” Immersive art experiences are rarely very educational in themselves, but, Kirk said, they might tempt people into education-oriented institutions. “School groups love coming into our experiences,” Kirk said. “They can run about, they can get enveloped with the color and the audio. They’re not necessarily learning anything, but we’re just introducing them in a different way, in some way. Hopefully, they’ll get something from it that would engage them further.”

Last year, Grande opened THE LUME Melbourne, which it touted as Australia’s first digital-art gallery. Still, despite that designation, the space is content-agnostic: Kirk hopes to bring in audiovisual experiences focussed on many different industries and subjects—science, music, history, sports. Grande’s goal is to attract the largest possible audience, but Kirk thinks that there is also room for experimentation. “There could be certain displays that present N.F.T.-based art, created by digital artists of today,” he told me. (Art Blocks, a platform for digital art, recently opened an N.F.T. gallery in Marfa, Texas.) “It could be the digital equivalent, should we say, of Vincent van Gogh, Leonardo da Vinci, something like that, who would then have their own presentation of their art in a large-format environment.” In the future, he suggested, such generalist digital spaces might become fixtures of major cities—institutions on par with museums, art galleries, aquariums, and zoos.

n January, I visited “Immersive Van Gogh” in downtown San Francisco. The show is housed in a trapezoidal, two-story event space that previously served as a Honda dealership and is currently slated for demolition, to clear the way for a towering condo development. The building was once home to the Fillmore West, a famous, short-lived concert venue at which Aretha Franklin, the Grateful Dead, Miles Davis, and Fleetwood Mac performed. Today, it is operated by Non Plus Ultra, a company that specializes in “reactivating” commercial spaces. The building also contains the Unreal Garden, an immersive experience in which visitors don mixed-reality headsets and navigate a blandly psychedelic artificial environment.

Outside, a bouncer watched the door, presiding over roped stanchions, behind which no one stood. Inside, the space had an air of transience, as if the tenants had made only a half-hearted effort to rise to the occasion of their own existence. In the stairwell up to the ballroom, a mounted television flashed a medley of statistics: “56,000 FRAMES OF VIDEO. 400 IMAGES CONTRIBUTED FROM THE WORLD’S FOREMOST ART GALLERIES. 40 PROJECTORS. 11 SERVERS.” At the top of the stairs, a plastic mannequin, wrapped strategically in plastic sunflowers, had been placed in an inviting position beneath a mural that read, “We are surrounded by poetry on all sides.” The mannequin’s wrist seemed to be sliding away from its arm at the joint. A potted fern stood nearby, wilting.

Inside the ballroom, a looped, thirty-five-minute projection was underway. Edith Piaf’s “Je Ne Regrette Rien” blared from overhead speakers as a yellow sun—cropped from “Sower with Setting Sun,” and given new life with animation software—swept from wall to wall. About twenty people relaxed on white benches placed in illuminated circles meant to encourage social distancing; two women sat on the ground, talking in hushed tones. I wondered whether the surging popularity of these exhibits might have to do with how they offered a predictable, roomy environment at a time when other indoor public spaces could feel claustrophobic and contagious. (Seeing original paintings, of course, at museums like MoMA and the Met, means standing in a crowd.) An enormous “Girl in White” scrolled past, soundtracked to a cello suite. Her face puckered and folded like a sock puppet’s as it slid across the molding. I found an empty circle, sat down, and stared at the wall.

The credits rolled, and the sequence began anew. Sketches of cicadas swarmed the room, buzzing. Smoke rose from the table in “The Potato Eaters.” Isolated objects from “Bedroom in Arles” rippled across the walls to moody electronic music. At one end of the room, two young people were palming each other’s knees with deep intention. I took a video of saturated light passing over a fire extinguisher and tried to summon a feeling. All that came to me were lines from John Berryman’s “Dream Song 14,” in which the speaker quotes his mother:

“Ever to confess you’re bored

means you have no

Inner Resources.” I conclude now

I have no inner resources, because I am heavy bored.

The poem was in my mind because, a couple of days before, my friend had idly recited it from memory over the phone while holding her infant—a genuinely thrilling and immersive experience.

The music intensified, and the animations chugged toward their denouement. From the depths of “Starry Night Over the Rhône,” several of van Gogh’s self-portraits wiggled murkily into view, his face superimposed over the river and the sky. Was this really the dawn of a new cultural form? Installation art is old, and so is the critical debate over its meaning and value. Are art stacks, commercial or prestige, primarily an economic idea—a business structure in search of practitioners? The principle features of the model—scalability, financialization, vertical integration—are financial. It seems inevitable that these values will infuse the work, in the same way that N.F.T. art, born of a technological possibility, has its own visual culture, one that appears to emphasize algorithmic generation and proficiency in graphic-design and rendering software. The work looks commercial, because it is fundamentally about commerce.

On the way out, I was routed through the building’s spiralling garage, part of which had been converted into a gift shop. Since 2017, Lighthouse Immersive, the production company behind the show, has sold over three million tickets, and earned millions of dollars in gift-shop revenue. My ticket, the cheapest available, had cost nearly fifty dollars; the most expensive option, a ninety-dollar V.I.P. package, included a cushion and a poster. What we were paying for was proximity—not to the paintings themselves, but to the idea of them. The exhibit was a technology demo that traded on mythology. True immersion remains an unusual aesthetic achievement.

I walked down a ramp and through a side exit, and emerged onto an outdoor parking area. I had forgotten that it was daytime. The sun was warm; the sky was clear. Spring came early to San Francisco this year. This is unsettling, like getting away with something—it should be raining—but it’s hard not to luxuriate. I was hit with the full force of an expiring afternoon. There were errands to run, phone calls to make, things to worry about. In a city where tech-driven business models routinely flourish and fade, I had the sensation of having witnessed yet another bid for the future. It was a relief to leave it behind.