Museum Workers Share Their Salaries and Urge Industry-Wide Reform

Written by Zachary Small and published originally by Hyperallergic, June 3, 2019.

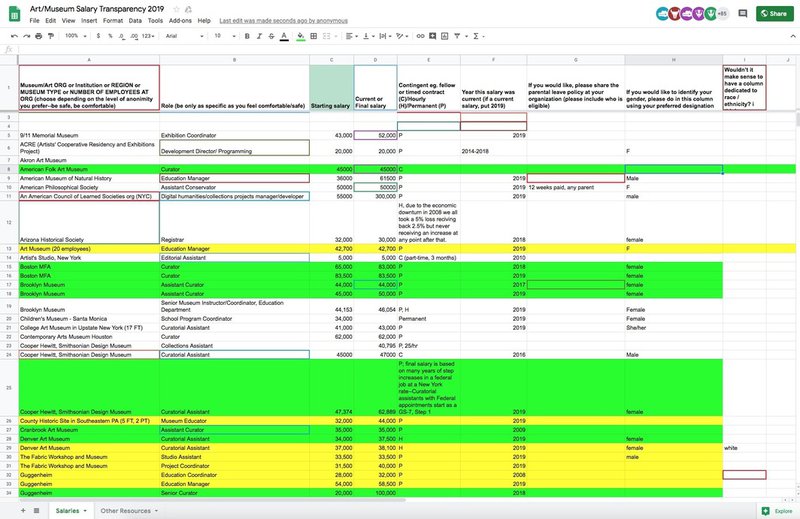

Transparency can be radical, especially in an industry as financially oblique as the art world. Last Friday, museum workers began contributing to a Google Spreadsheet documenting their place of employment, salary rates, and demographic details like race and gender. The data points offer crucial insight into the economic hierarchies inside some of the world’s most prestigious museums.

Entitled “Art/Museum Salary Transparency,” the spreadsheet has attracted more than 660 submissions after it was published just three days ago. The public push for disclosure adds to an insurgent movement of artists and museum workers who wish to address the economic inequalities manifest in cultural institutions. Tensions have increased in recent years as museums embark on multimillion-dollar expansion projects, arts staff unionize across the country, and activists scrutinize the ethics of institutional funding.

“Just be brave and add your information to the list,” suggests Michelle Millar Fisher, an assistant curator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. She and her colleagues created the spreadsheet to increase solidarity among arts workers, many of whom struggle to make ends meet on their salaries alone. They were inspired by the Adjunct Project, Kimberly Drew’s keynote address at the 2019 American Alliance of Museums conference, and the ongoing POWarts salary survey.

“I’ve been an adjunct, a nanny, a cook — and lots of other things to support myself,” Fisher said during a phone call with Hyperallergic. The assistant curator has also previously written for this publication about parenting and labor in the art world. “All of us in the arts have had to take other jobs, and that will likely always be the case.”

Because the spreadsheet entries are published anonymously, Hyperallergic could not independently verify the accuracy of all the listed salary information; however, the information does match long-running perceptions about pay in the field. (New entries are being added through this Google Form.) Although positions like curatorial assistant are competitive and prestigious entry points into museum work, the pay is relatively low with starting salaries running between $30,000 and $50,000. By comparison, the select few who rise through the ranks to become chief curators at major museums can expect to make well within six figures.

“As the spreadsheet reveals, more and more institutions are relying on contingent labor — whether fixed-term project positions or fellowships,” explains one of Fisher’s collaborators who asked to remain anonymous because their museum position is non-permanent. “While the people in these roles are given equivalent responsibilities to those in permanent positions, they generally receive a lower salary, and their positions are by definition precarious.”

Many of these positions also require a substantial investment in education. Increasingly, museums expect their curators to have Master’s and PhD degrees with specializations in their fields before being considered for such a position. And even then, opportunities for advancement are minimum.

Maggie Stenz understands how difficult it is to thrive in the museum world. After earning her PhD in art history, she worked for a decade as a curatorial research associate at the Brooklyn Museum but later left the industry entirely because of low pay and difficulties with career advancement. “When I was looking to move up into a full-time curatorial position, there were only about 10 positions per year in the US in my area of expertise,” she explained to Hyperallergic over email, “and for each opening, there must have been dozens of qualified applicants.”

Those who contributed to the spreadsheet hope that transparency will lead to some sort of remuneration reform that may also contribute to further diversifying the field across socioeconomic categories. Even as museums are described as “cash-strapped” and expensive to run, their employees (and the public) are increasingly aware of how infeasible it is for people from low-income or middle-class backgrounds to work in such institutions without other independent sources of income.

For her part, Stenz decided to contribute to the salary transparency spreadsheet to undo some of the secrecy that plagues the industry. More recently, she has worked in state and city government, which must post salaries as a matter of public record. That means she doesn’t waste time going after a job she might love, but can’t live on. “I worked for so little for so long, I need to make more money now,” she said. “It’s a horrible job once the the realization dawns that your dream job will never materialize.”