Leadership challenges in arts repatriation for museum governance

By Carolyn Campbell, Marc Ventresca and Alison MacDonald.

Originally published by University of Oxford.

Museum boards and senior executives face a distinctive set of challenges today, with consequences that shape anew the core mission and activities of 21st century museums. In our current research at the University of Oxford, we explore the nature of controversies regarding the repatriation of artifacts that reach board level and have impacts on the fate of museums. We draw on a range of content from several of the world’s leading art museums – archival materials, board documents, recent and upcoming interviews with over two dozen senior museum leaders, and museums on the receiving end of the repatriation process.

This concept of repatriation can involve many activities crucial to the modern museum, from sourcing and acquiring new materials for exhibit, to returning materials and artifacts sourced by dubious or today unacceptable means to the people from countries wherein the artifacts originated. The controversies over repatriation issues occupy more and more time on the agendas and informal work of boards and executives. And, as evidenced in the early findings of this study, these controversies are establishing a new era of best practices that shape the future of the museum as a cultural institution, educational platform and venue to preserve and sustain cultural and archival materials.

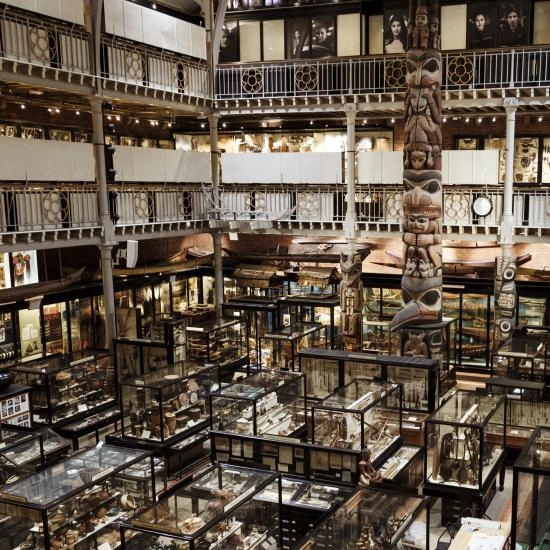

Museums in their contemporary format and focus came into view over 100 years ago, at the interconnection of new traditions in the social sciences like anthropology and fascination with ‘the past’, the impact of wealthy benefactors and governments, and new kinds of questions about the arts and culture. The broad outlines of display, curation, conservation, exhibition and education took shape in a series of generational struggles among museum elites and benefactors.

This era of relative institutional stability provided museums with a reasonably settled mission and cultural role at the nexus of culture, politics, civil society and history. However, starting in the 1970s and escalating in the 1990s with more and more public controversy – including fresh new concerns about the Rosetta Stone at the British Museum - there are now significant public challenges based on questions about the provenance of artifacts on display in leading Western institutions. The 1970 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act and the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the ownership of cultural property established two major policy documents informing these debates; more recently, Emanuel Macron, President of France, made repatriation part of his electoral platform and commissioned the highly public Sarr/Savoy report on the issue in 2018.

These early deliberations over, for example, the Parthenon Sculptures (aka ‘Elgin Marbles’) have now been amplified by broader debates over cultural appropriation, mobilisation by civil society movements and communities, and a new uncertainty about the role of the museum. Laura Van Broekhoven of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford says these debates and resulting ideas are leading to rich new questions for museum professionals and other stakeholders. She states ‘if we truly want to be inclusive and honour humanity’s place of knowing and being, then we ought to be responsible for undoing past cultural violence and understanding other ways of being’. In another interview, Tristram Hunt, Director of the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London, affirms that it is vital for museum leaders to be transparent, accountable, globally engaged, and mindful of having a digital footprint.

The debates and the associated agenda for boards and senior executives has started to change the nature of museums. And indeed, these are debates. In practice, museums around the world have been galvanised to engage and act on these issues. But the framing of the issues and the actions taken by boards, or not taken, vary rather a lot. Our work captures this context, both of the strong social and cultural claims, and the controversy and ambiguity about what to do next. This research highlights five core issues in the conversations about repatriation:

1. Legal

Museum leaders and lawyers have long relied on cultural acts and legalities to assert legitimacy of ownership of cultural property by institutions. But, although there has been a change in viewpoints around repatriation, the legal tools to help have not been introduced. Now, in the UK there has been a breakthrough. The February 2022 Charities Act is framed to essentially allow legality to catch up with morality, giving museum trustees another tool to return cultural heritage, the lever being that if trustees believe an object to be morally misplaced, they can deem it returnable. This leaves room for trustees to decide what counts as a moral obligation to repatriate, which must be documented in minutes. There are further considerations coming to tighten the criteria for trustees and the potential to have them shift that responsibility to a third party. Further, the Charities Act could be advantageous for Lord Vaizey’s new Parthenon Project board work, established to return the marbles to Greece. Both the British Museum Act of 1963 and the National Heritage Act of 1983 have been used as the legal premise to resist repatriation. With the introduction of the Charities Act, there could be a formidable legal response.

2. Safety of objects

Arguments against returning cultural property frequently claim that objects will be safer in western museums, rather than returned to home regions where they could have historically been damaged or destroyed, or where that could happen in the future. This contention is being challenged. For example, the Acropolis in Greece is a significant museum that is just waiting to house the Parthenon Sculptures. The phrase 'cultural arrogance' is now being levelled rhetorically and informally at the notion that objects would be unsafe if returned to their place of origin, especially considering the potential for any museum in the world to suffer from an attack.

3. Cultural understanding

Indigenous peoples share that cultural objects are sacred, and can be living beings or considered as ancestors. Therefore, concerns abound regarding the way objects are displayed. This includes the issue of holding museum events adjacent to the exhibition spaces of these objects. Moreover, the 'livingness' of cultural objects means that they are reported as missed at home, from ceremonies and community. For example, the Manitou Stone at the Royal Alberta Museum (RAM) in Canada fell from the sky in Hardisty on an unknown date, started travelling across the country as a 'taken' object in 1866, and was eventually brought back to the RAM where it was enveloped in controversy, consultation, ceremony and elaborate display. Recently, in what is being reported by Indigenous representatives as a major step forward, the Alberta Government announced that the Manitou Stone will go back to its home region in a planned $7.5 to $10 million geodesic dome and prayer centre.

4. Reputation

Civil society pressure to address sensitive and topical issues, as evidenced in media stories, social media posts, academic research, talks and book tours, has led to more engagement with stakeholders and audiences. Dan Hicks’ 2020 book The Brutish Museum received considerable attention for calling out hesitancy to repatriate the Benin Bronzes, and as we have seen, many bronzes have been returned of late.

Top of mind in leadership is navigating the reputation of the institution. Sue Fruchter, Deputy Director for Operations/COO of the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), says that ‘all museums are struggling with relevance and community engagement. Who is their audience, who should it be, and how ought they engage with that audience?’ The ROM board prioritises how to engage and grow from the work done in other areas of their professional or personal lives, and asks what can we learn from each other?

5. Politics

Political pressure, counterpressure and oversight is reaching into museum governance and operations. Formidably, the Sarr/Savoy report unequivocally argued for the return of cultural property to home regions. President Macron’s rhetoric did the same bringing pressure to leaders to change along with the change in societal values. The Ed Vaizey appointment in the UK is already stirring the House of the Lords and raising questions about government priorities, responding to engagement from both the British Prime Minister and the Chairman of the British Museum, George Osborne, on both sides of the issue of the sculptures’ return.

For boards, trustees and senior executives, three core considerations are emerging today:

Firstly addressing the concept of loss. Filling the void as cultural objects return home also provides an opportunity for museum leaders to stretch creatively and innovate new business models. Van Broekhoven talks to boards and donors about not seeing repatriation as a loss but working towards reconciliation and redress. For her, there is generative work in conversations with communities about return and redress - establishing trust, better care for objects, listening and thinking with stakeholders, and opening conversations into new fields of study. This includes methods of co-curation, and looking at cultural objects in a new way. Some items in the Pitt Rivers for example, have not been looked at in 100 years, and fresh study can bring new life and ideas to this cultural field. Further, there is the matter of executive, board, and trustee fiduciary responsibility to the institution. If many artifacts are repatriated in the future, it is feasible for leadership to have concerns about fiscal loss due to a reduction in visitors. This is also an opportunity for museum leaders to think more strategically, and creatively about the purpose, mandate and educational responsibilities of the institution.

Secondly ESG (environmental social governance) principles influencing both the governance and managerial direction of institutions are adding to the tension of who and how donations will be received and displayed. A correlation between falling into alignment with social pressure from civil society and audience acceptance of mandate is increasingly real. In a twitter search on repatriation, images appear of signs beside cultural objects declaring that the object should go home. In an adjacent but informative issue, public pressure on museums to resist or reverse donations in the name of companies that fall outside of public goodwill is assuredly an agenda item at both executive and board tables. Consider, if you will, the name Sackler, a wealthy family who donated to many museums and galleries but whose name is now synonymous with the opioid crisis in the USA. On the matter of boards themselves, members are under increased scrutiny, such as the 2019 protests around a board member of New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art whose company sold tear gas, resulting in his subsequent resignation. With this, it seems fundraising work has expanded from simply an operational portfolio stream to a public policy and civic engagement stream, adding immeasurably to the complexity of this function.

Finally the UK’s 2022 Charities Act will be a game changer in how the oft standing agenda item on repatriation at board meetings is governed. Negotiating the transition to a discussion on moral authority is complex, and precedents in comparable fields will be necessary. As recently as February 2021, Hunt said that legally, the V&A cannot repatriate, but they can do substantial partnerships and long-term loans. He says the board is interested in this work both intellectually and reputationally and must be engaged in the conversation actively. In thinking about Hunt’s comments, it is possible that the intellectual side of the repatriation debates is about to be seen through a new lens, and this may require boards and executives to look anew at the skills matrix of the board to guide these conversations.

The controversies and debates evidenced through the issue of repatriation in world leading museums demonstrate a complexity that is germane to leaders across professions and sectors, especially in the navigation of large public institutions. Museums will be a case to watch as they are by nature entirely public, and representative of world cultures and beliefs. As museum leaders, board governors and trustees navigate this complexity, examples of solutions, pathways and fresh ideas will emerge and provide insight for leaders in the field of arts and beyond.

Authors

Carolyn Campbell is a doctoral student at the University of Oxford and a noted painter, with a long professional history in public service and higher education. She is currently the President and CEO of a large public college in Canada. Marc J Ventresca is on faculty at Saïd Business School, an expert on innovation and strategy, and a Governing Body Fellow of Wolfson College. Alison MacDonald is a member of the senior leadership team at Oxford University Department for Continuing Education (currently Interim Deputy Director) and a Fellow of Kellogg College. Her research interests include Roman urban and rural landscapes and issues concerning the restitution and repatriation of cultural objects.