"For me, curating is about telling stories, and how they are told is equally important"

How did you become a curator of contemporary African art?

I’m an artist by training. This is important because, as a practising artist, I had some experience of exhibiting my own artwork and of working in an art museum very early on in my career. This gave me a good foundation in becoming a curator.

Under apartheid, where racial discrimination was legal, many Black artists did not have the opportunity to exhibit their work in museums or even commercial galleries. At a certain point, I started to use my skills and experience to tell some of those South African stories that were not being told.

In 2004, I curated 79-year-old photographer Ranjith Kally’s first solo exhibition; he had been working in the profession for 60 years. Born in 1925, his work reflected his obvious talent and also revealed hidden histories. The show at the Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg received incredible media coverage, and many museums and collections subsequently acquired his work. It was rewarding for me to see him receive the deserved recognition while he was still alive. Together we collaborated on 7 exhibitions in 5 countries: South Africa, Mali, Spain, Austria and Reunion Island (France). You can read more about Kally’s work in an article I wrote on his death in 2017: https://africasacountry.com/2017/06/the-great-opus-of-small-bobby

Later in 2012-13, I curated exhibitions on the work of South African artist Peter Clarke in Dakar, London and Paris. At the time of the exhibitions, Clarke was 83 years old. He was a talented artist but because he was Black and lived most of his life during the apartheid years he had not received the proper opportunities and exposure. See information on the exhibition we did at INIVA in London:

https://www.e-flux.com/announcements/33236/peter-clarke/

In 2006 I did a project from the Drum magazine archives — the internationally renowned magazine that empowered Black writers and photographers in South Africa and later in the rest of Anglophone Africa, in places like Accra, Lagos, Nairobi, etc. The photo exhibition focused on the Indian community in Durban, where I was born, revealing the multiple and complex identities within the community and challenging racial stereotypes. It was a way of learning more about my family’s history (in South Africa since 1878) and the unofficial stories of the broader community, presenting to the South African public, via photos, the oral histories that I heard about from my parents. Due to the legacy of apartheid South Africans know little of each other’s histories across racial lines.

More on this exhibition here: http://www.enterpix.in/feature/passages/the-indian-in-drum-magazine/

Soon after the Drum exhibition and book, I was appointed director of the South African National Gallery, a position I held for six years (2009-2015). In my first year I curated a very large exhibition (of 580 art works) entitled From Pierneef to Gugulective that used all 12 gallery spaces of the museum. Some artworks were from the National Gallery's collection and the rest were loaned from 48 different collections from around the country. The show was meant to be representative of South African art over a century from 1910-2010, including the apartheid years (1948-1994). The exhibition received local and international attention, and I was invited to MoMA (New York) and the Tate Modern (London), and numerous other institutions in other countries to speak about it. https://artcritical.com/2010/06/29/dispatches-capetown/

In 2016 I curated a public art project called Any Given Sunday in Cape Town, in the city and surrounding townships, with socially engaged artists. It was aimed at the Black working classes, who generally don't have access to art and museums due to the lack of art education among other historical factors. The project was funded by Pro Helvetia – Swiss Arts Council and the Institute for Contemporary Art Research (IFCAR) in Zurich. It is fully archived online with a publication that can be freely downloaded: https://www.draftprojects.info/projects/cape-town.html

Most recently I curated a public art project on contemporary art from Africa and the diaspora in Saint-Denis, the Parisian suburb. The project included very established artists such as William Kentridge, Samuel Fosso, Barthélémy Toguo, Mary Sibande, Jelili Atiku and other artists who are gaining a reputation for their work, namely, Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Cheikh Ndiaye, Lebohang Kganye, Kudzanai-Violet Hwami. For more see: https://www.e-flux.com/announcements/414078/neuf-3/

How do you understand the figure of the art curator, how do you develop it in your projects, and how would you describe it from the perspective of the contemporary African art curator?

For me, curating is about telling stories, and how they are told is equally important. Research helps me understand which artists and artworks are appropriate within the theme/s I want to highlight. The space is important to consider too. For example, does the site contribute any meaning to the theme being addressed? What are the conversations between the artworks in the space? What are the sub-themes of the exhibition and how do they relate to each other in a very large exhibition?

Text is also important and is a way of communicating with the audience that allows me to give more information about the story I want to tell, and the connections between the different subtexts to the overall story.

As a curator working with contemporary art from Africa and the diaspora, I can say that there is much work to be done. For a long time in the West, African art has been represented through masks and statues. This can be traced back to the ‘discovery’ of African masks by the European avant-gardes in Paris. For example, in Picasso's 1907 painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, two of the women's faces are depicted as masks, and from that moment on, Western art changes, and masks become associated with the (Western) modern avant-garde art.

For instance, when South African artist Ernest Mancoba arrived in Paris in 1938, he was expected to be familiar with masks even though there was no mask tradition in South Africa.

This idea did not change for a long time! Exhibitions on African art in the 1980s and 1990s and even as late as 2010 in the United States or France, meant representations of traditional arts from Nigeria or Benin or Congo, etc. The more exotic, the better! In the meantime, modern and contemporary African art has been evolving, both absorbing and rejecting influences, in the different contexts of university art schools, private art spaces, community project spaces and among artist collectives, self-taught artists, traditional practices, etc. So African art was constantly changing, developing its own artistic languages.

In the last 10-15 years, more attention has been paid to modern and contemporary African art, thanks to art fairs such as the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair or the Johannesburg and Cape Town art fairs, or the more international art fairs such as Art Basel, that have now included more African art galleries in their representation. This has contributed to making contemporary African art better known to the world. So, modern or contemporary African art is not something new; it's only that the West is now discovering and acknowledging it.

For many curators working in the field of modern and contemporary African art, their goal is to make these kinds of marginalised artistic histories visible, through research, publications, and exhibitions.

I am reluctant to generalise here because each curator has his/ her/ their own style, philosophy and aims. Nonetheless there are so many good artists from previous eras — whose artworks and narratives have been silenced due to discriminations and biases — that still need to be brought to attention; this is the work that still needs to be done — a recovery of modern and contemporary African art histories.

Is there a tendency to move away from the concept of continental African art, and start referring to African art from different countries and regions?

I think the terminology of contemporary African art is problematic. It's like talking about European art, which means nothing! In an interview I did with Simon Njami — writer, curator, independent art critic, and artistic director of the 12th and 13th editions of the Dak’art biennales (2016 and 2018) — he said that there is no such thing as contemporary African art; it does not exist!

The term is problematic because it homogenises art from the whole of the African continent; it was coined to package African art for the West that usually refers to the continent ‘as a country’. On the contrary Africa is a very diverse continent, with different cultures, languages, and ethnicities, etc. and likewise the art within the continent is varied from Kinshasa to Marrakech from Kampala to Dakar, from Accra to Johannesburg, from Cairo to Douala and then of course there is the diaspora from Port Louis in the Indian Ocean to Kingston in the Caribbean, from Paris to São Paulo…

There is a tendency for curators who live in the West to group together works from the African continent, and they do it for a Western audience. So some of the problems lie in who's doing the exhibition and whom they're doing it for.

The term contemporary African art is very entrenched. It would be more accurate to speak of contemporary art from the African continent and the diaspora.

Today there are the established biennales, such as the Dak’art biennale in Senegal, the Bamako Encounters biennale of photography in Mali, and other smaller biennales such as in Kampala (Uganda), Cairo (Egypt) and Kinshasa and Lubumbashi (both in the Democratic Republic of Congo), among other. Alongside this there are independent initiatives — such as Raw Material in Senegal, and Njelele Art Station in Zimbabwe, Bandjoun Station in Cameroon — that are doing exciting things, despite limited resources.

What are the issues that African artists are currently dealing with?

It is true that many artists on the African continent deal with political and social issues because these concerns are all around them and affect their lives on a daily basis. Let’s look at South Africa, coming out of the context of apartheid in 1994 — one of the last countries in Africa to gain majority rule and self governance — and now experiencing new challenges in the post-colony. In the past many artists used their art to expose and give voice to the injustices of apartheid, bravely depicting what the state censured.

Today a new generation of artists are tackling other inequalities and discriminations closest to their personal concerns and identities: violence against women, gender equality, sexual orientations, minority rights, religious intolerance, erased histories, xenophobia, etc. These new forms of activism are necessary and relevant in the now.

Many African countries, such as Senegal or Nigeria, gained independence much earlier, in the 1960s. At the same time, the South African art infrastructure, in terms of art schools, galleries, and museums are more developed than most of those in other countries on the continent, making it easier perhaps for international collectors to identify artists' work and purchase and transport art. The art fairs in Johannesburg and Cape Town and the numerous commercial art galleries contribute to South African art circulating more widely.

Do African museums showcase the issues that connect with the communities where they share a geographic context?

Museums have a role to play, but we have to understand that museums in Africa are not the same as museums in Europe, and they perhaps do not always occupy the same function as they were originally intended. This is mainly due to the colonial education system, which privileged crafts over fine arts for the Black majorities in Africa. Much of that education did not change when the countries were liberated, except perhaps in cases like Senegal where poet Léopold Sédar Senghor—who was also president for 20 years, from 1960-1980—made many positive reforms in favour of the arts, in what is referred to as the Senghorian era.

In South Africa, it is the elite schools that teach fine arts. Moreover, many township (read Black) schools still lack proper art education facilities and materials, meaning that the museum-going public is a mainly older white audience. The new young Black audiences are those who have engaged with art at schools and universities, but the majority of the Black population in the country still do not visit museums in sufficient numbers. Thus, museums cater to a small minority of locals and of course tourists, especially Europeans and Americans.

One also has to question whether museums are the only models relevant to the African situation? Without this background in art education, most people are intimidated by contemporary art and feel alienated in museum spaces. Some private museums have a very high admission fee for the local contexts that they are in, so they deliberately exclude the majority of the Black working classes, making it more difficult for people from those communities to visit the museum. These museums operate as if they are in New York or London or Paris without consideration of their local context and the audiences they can potentially ‘serve’.

These are challenges that my public art projects Any Given Sunday and neuf-3 try to respond to.

So, how do you attract people to museums when they have never been before?

One way to attract audiences is to reflect people’s histories — which can also be done through artists from their communities (for example, Peter Clarke and Ranjith Kally) — so that people can identify with the art and the depictions being displayed. It's important to ask which communities do the museums want to attract or speak to? What stories does the museum want to tell? The exhibition programme and the related public events are crucial. Acquisitions are also important; it indirectly tells the public where the museum’s priorities lie and for whom. This gives a hint of the museum’s regard for its immediate public. That is, those potential publics in its direct vicinity that can regularly visit and support. When you have exhibitions that speak to specific communities, people from those communities will visit the relevant museums.

In 2011 we held a retrospective exhibition at the South African National Gallery on the work of Vladimir Tretchikoff, a Russian artist who fled Europe during World War ll and eventually arrived in South Africa in 1946. Tretchikoff mainly painted the Black working classes of Cape Town: the flower sellers, the hawkers, the workers, and so on. He was excluded from many elite art institutions throughout his career, and unable to exhibit in the more formal galleries and museum spaces, he made colour prints of his paintings and had exhibitions in departmental stores. People bought the graphic prints of his paintings by the hundreds of thousands, and he became very popular. So we took the decision to be involved in producing a retrospective on the artist’s work, knowing full well the controversial debates that it could provoke, but with the idea of having a transparent discussion about these issues rather than pretending that they didn't exist. During the exhibition, we had a 107% increase in the visitor numbers over the previous year and a 173% increase in visitors over two years — due to the “From Pierneef to Gugulective” exhibition of the previous year in 2010. And significantly, with many new Black audiences that visited the art museum for the first time.

Throughout my career it has been very important to me to connect my exhibitions with the everyday public. While practising as an artist I didn't make art for the art world or art market but rather for the people I knew and the community I came from, those who inspired my work. This is due largely to my experience of coming from a working-class background under apartheid. I firmly believe that everyone can benefit from art and that, in the African context, art has the potential to reach a much wider audience than it does. But it is up to the artists and curators and museums to address these issues. We have to ask for whom we are making the art and exhibitions? Which audiences should we be focussing on?

In the conference you organised entitled "Pioneers of Contemporary African Art", promoted by the l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art (French National Institute of Art History), you focussed on the artists, movements and collectives of the 1960s and 1970s. Why this period?

In 2021 I was invited by the INHA (Institut national d'histoire de l'art) in Paris — which generally deals with themes of European art history — to conceptualise a conference on contemporary African art, and identify the themes and participants. This was intended to be part of the African Season festival in France, an initiative of French President Emmanuel Macron.

Given carte blanche I decided to focus on the developments in African art in this period because, in France and perhaps in Europe, many people have the idea that contemporary African art started in 1989 with the exhibition Magiciens de la Terre in Paris.

There were many precedents in art on the African continent in the 1960s and 1970s, so the conference sheds light on talented artists like Uche Okeke from Nigeria, and David Koloane from South Africa, publications like Black Orpheus, art schools like the Nsukka, and artist collectives like Agit'Art in Senegal.

It also concentrated on key moments in the history of pan-African artistic and intellectual solidarity, like the First International Congress of Black Writers and Artists (Paris, 1956), the First World Festival of Black Arts (Dakar, 1966), the Pan-African Festival also known as PANAF (Algiers, 1969), the Festival of Arts and Culture - FESTAC (Lagos, 1977), and the Culture and Resistance Festival (Gaborone, 1982). For more information on the conference context and programme see: https://www.inha.fr/fr/actualites/actualites-de-l-inha/en-2022/pionniers-de-l-art-africain-contemporain.html

My proposal was a snapshot of that time. Naturally, I had to make some selections and only a few of the most influential artists, collectives, publications and festivals of that time could feature in a two–day conference, which was also dependent on speakers’ availability. The recordings from the conference are now online:

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLsl8NWzVv6T0JdAOYr3x3KA1rQcadZHWa

Could you explain to us the essence and purpose of your neuf-3 public art project?

In 2018 I came to Paris for six months on a residency at the Cité Internationale des Arts — thanks to a grant from the French Institute in Paris and Johannesburg — to do some research on contemporary African art linked to a long-term research project that I’m working on.

Paris attracts individuals who are still looking for this artistic myth that the city is known for. In the 1920s and 1930s when the city was a very open space, artists — such as Cuban Wifredo Lam, South Africans Ernest Mancoba and Gerard Sekoto, and Sayed Haider Raza from India — came to live in Paris and to be in contact with avant-garde artists. The city also attracted African intellectuals like Senghor, Aimé Césaire and Frantz Fanon. Later, in the 1960s, African American writers such as Richard Wright, James Baldwin and Chester Himes, also settled in the city.

At the same time, Paris’ institutions were not buying or exhibiting modern or contemporary African art because they were still trapped in this idea of African art being represented by masks and figures.

In 2019 when I took the local RER train to Saint-Denis, just 10 km from the centre of Paris, I saw that the demographics shifted. The majority of people on the train were immigrants from West and North Africa. Saint-Denis, is of course famous for many things, such as the historic Basilique de Saint-Denis — which dates back to the 5th century and its later Gothic architectural style, dating to 1145 — and for its diverse community of mainly African immigrants. The basilique is a great source of pride for the dyonisiens — as the citizens of Saint-Denis are referred to.

On stepping out of the train station in Saint-Denis and watching the streams of people flow towards the city centre, I thought it could be an ideal place for a project like Any Given Sunday — that I did in Cape Town — with the participation of African artists. This is how the idea of “neuf-3” was born and Le 6b artist residency in Saint-Denis supported me as a partner. As it was my idea I fundraised for it and finally another 7 partners joined me on the project: musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac; Heinrich Böll Stiftung, Cape Town; the French Institute of South Africa; la ville de Saint-Denis; Christie’s (Paris); the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire Paul Eluard de Saint-Denis; the Center for the Study of Slavery & Justice (Brown University, U.S.A.). It is important to mention this because without that support the project would have not been realised. I also had amazing unconditional support from the municipality of Saint-Denis, who incidentally, are campaigning for Saint-Denis to be European Capital of Culture in 2028.

Once I had sufficient funding to realise the project I started to contact the artists, who all loved the proposal and immediately accepted to participate. It is a project with 13 artists, 34 artworks, 2 performances, and more than 30 guided tours (the latter done by yours truly). It was a labour of love and took almost two years from conception to realisation. The aim of this initiative was to promote contemporary art from Africa and the diaspora; to acknowledge the history of African artists in Paris; to pay homage to the generations of African communities in the French capital over the centuries — histories that are largely rendered invisible.

When conceptualising this exhibition, I was clear about the audience I wanted to address. It was firstly for the African communities of Saint-Denis, which are part of a broader cosmopolitan public. Saint-Denis is also a special place in Paris and in all of Europe, for its large African community, and I had the citizens of this suburb in mind when I conceptualised this project.

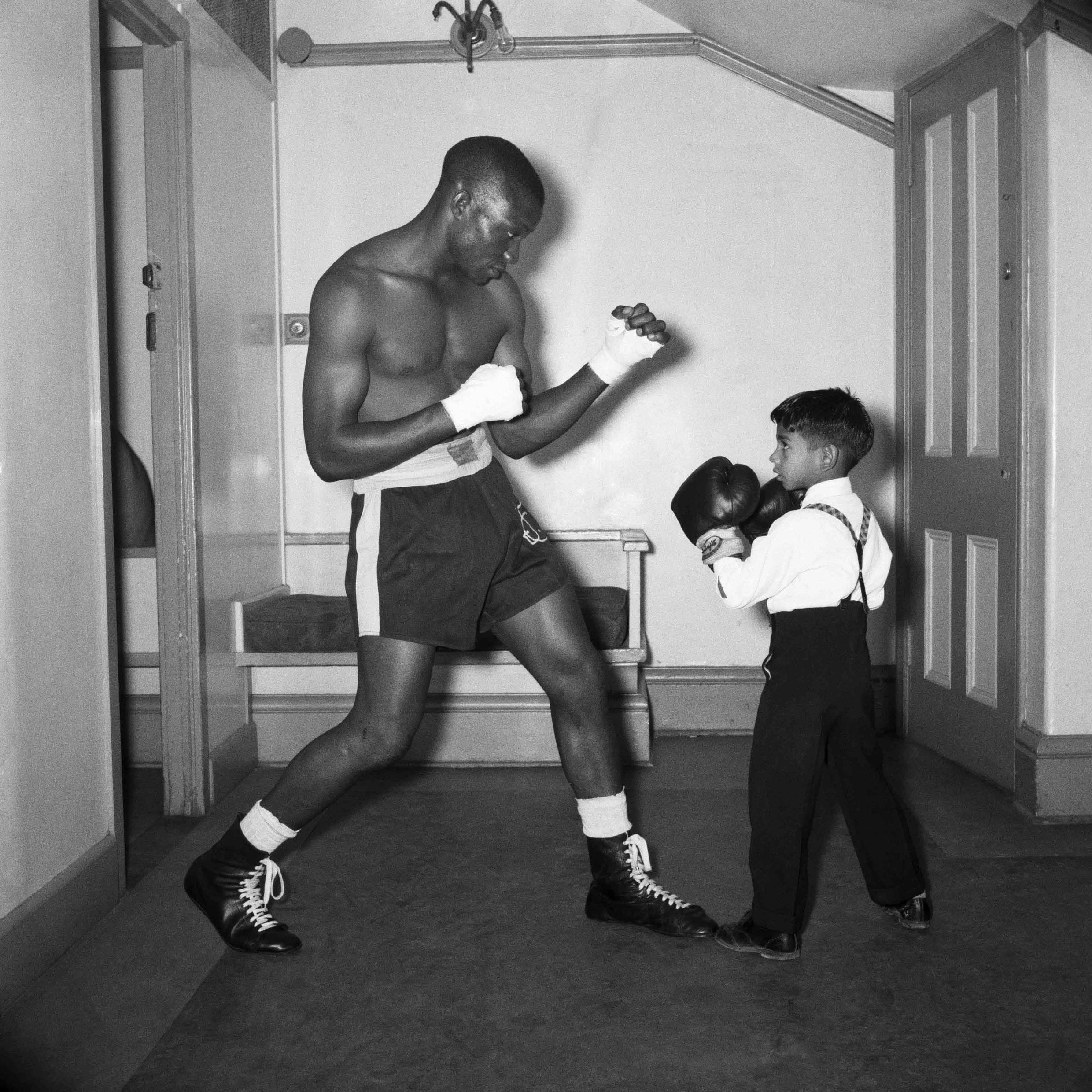

I selected artworks that people on the street could relate to, that they could identify with, that they could see aspects of themselves in. Some of the examples are: Samuel Fosso's “African Spirits” (2008) series — which are self-portraits after iconic Black figures such as Angela Davis, Nelson Mandela, Muhammad Ali, Patrice Lumumba, et al — William Kentridge’s Untitled (Frantz Fanon), 2016; Dalila Dalléas Bouzar's portraits of Algerian women in the series entitled Princesse (2015-16) — which is a reinterpretation of French military photographer Marc Garanger’s pictures taken in French occupied Algeria in 1960; Cheikh Ndiaye’s evocative documentary paintings of old cinemas in Dakar and Saint-Louis in Senegal from 2018; Kudzanai-Violet Hwami’s exquisite and intimate paintings from 2017 inspired from her family photo albums; Lebohang Kganye’s theatre-set photos (2016-18) that reimagine her family’s narratives; Barthélémy Toguo’s New World Climax (a print series that started in 2001 and is ongoing) that focuses on immigration issues experienced by Africans in France, symbolically depicted via huge and heavy sculpted wooden stamps. For more see the Instagram page: neuf3_public_art

All the artworks were displayed in the streets, near the train stations and tramways, and around the basilique, where there are concentrations and movement of people. I carefully chose each of the 16 sites over several months. (I moved from the centre of Paris to the suburb of Saint-Denis in January 2021, while still fundraising for the exhibition so I had enough time to walk around and identify suitable spots.) When we were putting up the artworks, people stopped in the street to ask questions because they recognised the figures in the artworks (Samuel Fosso) or related to the stories or representations in them. This was the intention behind the project: for people to see themselves and their histories in the artworks in their immediate environment — on their way to and from school or work, to and from the train station — so that it is part of their everyday experience. It is a way to acknowledge their history and presence, to recognise their humanity.

Is there still a long way to go to position African art and African curators in museums around the world?

This is a complex issue. It is not just about African curators but also about museum collections. African curators can bring a specific type of knowledge or skills to the African collections they are working with. The complexity lies in determining whether museums are ready to diversify European collections with African art that African curators can manage, conserve and care for.

In the United States, more African American curators are being appointed to positions, but there is also a need to diversify the collections of those museums. Curators should be given a mandate and a budget to acquire contemporary art from Africa and the diaspora (and modern African art too because the contemporary does not come out of nowhere – there is a continuity, a history). This would make more sense; otherwise, it becomes a kind of window dressing, a display in exoticism — like Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris.

African curators can bring African narratives, African histories, African values, African artists and artworks into the broader mainstream and into major European and U.S. collections — and not only these — which is necessary if we are serious about a level playing field where all cultures have equal value and accorded the necessary respect they deserve.

We know that the colonial hierarchy is linked to power, capitalism, and the exploitation of labour for profit. For example, African histories such as those of 14th century ruler Mansa Musa who ruled over the ancient kingdom of Mali — spread across what is today Mali, Senegal, the Gambia, Guinea, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, Mauritania, and Burkina Faso — and the written histories and scholarship of Timbuktu have been historically excluded, since it overturns the dominant colonial narratives of the last few centuries.

Prior to directing the South African National Gallery I worked on the ancient Timbuktu manuscripts for six years (2003-2009), and these documents tell a very different story of African peoples and societies than the colonial propaganda. This history is being rewritten now, albeit slowly, by a new generation of African scholars, and one hopes that it will occupy a more equitable space in world history. See the documentary on our project in Timbuktu concerning the manuscripts made by the Special Assignment magazine programme (2005): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Px51wvegeAs

The histories of African peoples and their arts still need to be recovered and told to deal with all kinds of inaccuracies that have been circulating over the last 400 years. There is much work to be done by scholars, historians, curators, and novelists in Africa and the diaspora who feel this commitment to do so.

Since when have you been a member of CIMAM, and why do you think it is important to be part of a professional community on a global scale?

I have been a member of CIMAM since 2013, so next year will be my 10th anniversary in this professional community. My first CIMAM conference was in Rio de Janeiro, and it was a wonderful experience. It introduced me to the world of Brazilian art museums and related networks. (That was the first time I met some of the CIMAM staff, like Inés Jover.)

I encourage people to apply for a travel grant because the CIMAM Annual Conference is an opportunity to get a glimpse of the country where the conference is taking place, to meet international museum professionals and attend presentations on current world issues, such as relevant political or environmental themes, with carefully selected international speakers to address these topics during the three-day event. I highly recommend it for all curators, whether working in museums or independent.

Throughout the year, CIMAM assists museum professionals with projects such as Museum Watch, which supports professionals working in museums when they are in difficulty. This committee is crucial, and this international solidarity cherished, especially during challenging times, because museums — being part of local and national cultural structures — are not exempt from the hierarchies, internal politics and power struggles. Having access to this support as a member of CIMAM is critical.