Censorship challenge looms for Australian head of new Asia art capital

Written by Michael Smith, China correspondent, and published originally by Financial Review, January 27, 2021

In 2012 Uli Sigg, a Swiss businessman, Sinophile and, eventually, his country’s ambassador to China, agreed to donate 1510 pieces from his collection of Chinese art to the yet-to-be constructed M+ Museum for Visual Culture in Hong Kong.

It was an announcement with a heavy degree of synchronicity. Sigg, who started collecting in the 1990s, has amassed what is believed to be the biggest collection of contemporary Chinese art in the world, numbering 2600 pieces.

M+ will be the biggest public gallery in Hong Kong and one of the largest in Asia with an ambition of rivalling, in terms of the breadth and quality of its collection, London’s The Tate, New York’s MoMA and Paris’ Centre Pompidou. Included in Sigg’s donation are 26 works by Ai Weiwei, arguably the most famous contemporary artist in the world and certainly the most famous Chinese-born critic of the government in Beijing.

That was 2012; now we’re in 2021. The M+ is in its final stages of construction and is earmarked to open in the second half of the year. And in Hong Kong, months of violent street protests have been quelled, Beijing’s national security law aimed at quashing China’s critics has been passed, protest leaders have been arrested. Will those works by Ai Weiwei, a symbol of resistance to Beijing, be put on display?

Ai Weiwei works have never been censored in Hong Kong, says Suhanya Raffel – the woman at the helm of M+. She then adds a nuance to her answer – censorship is a question that applies to museums around the world. “When we talk about issues of censorship it needs to be more thoughtful and calibrated about how public institutions are responding to very local pressures as well.”

As the scaffolding is taken down from the M+ building designed by Swiss architects Herzog and de Meuron, Raffel speaks in a way of someone mindful that history is being made around her.

Born in Sri Lanka, at 14 she moved to Australia with her family. After studying art history at the University of Sydney she worked at the Tate in the UK. Raffel then spent 20 years in curatorial positions at the Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art, eventually rising to deputy director.

She then served for four years as deputy director of the Art Gallery of NSW before moving to Hong Kong to become the executive director of M+. In 2019 she became the M+ Museum director, in effect the top job at the gallery.

Raffel says M+ will cement Hong Kong’s position as the region’s undisputed art capital. “No other Asian city could have done it. Hong Kong has always been a cosmopolitan city, a city that has worked and responded in various ways to the pressures of history and politics and society,” Raffel says in an interview with The Australian Financial Review Magazine from Hong Kong.

“New York has the most active and established art market in the world. London is second. Hong Kong often vies with London for the second spot. Those are two cities with very developed public infrastructure in relation to cultural institutions which balance the commercial world.”

M+, an enormous visual museum in a part of the world not known for its public galleries, will provide that same sense of balance, thereby evolving Hong Kong from a city where art is bought and sold, to a city that is a global capital of art.

The scale of M+, as is typical for China, is breathtakingly large. It will include a suite of cultural institutions and occupy 65,000 square metres of the West Kowloon Cultural District, which is on 40 hectares of prime real estate overlooking Hong Kong’s harbour.

At an initial cost of $HK21 billion, which has reportedly blown out to $HK70 billion ($11.6 billion), the district will include a dozen performing and visual arts centres and museums, including M+. It is the biggest cultural infrastructure project under construction anywhere in the world.

M+ already has an impressive collection of just under 8000 works from the mid-20th century into the 21st century. Australian artists John Young, Tracy Moffatt, Daniel Crooks and Fiona Hall are represented, and there are about 49,000 archived items which include architecture as well as design.

And, like the thousands of works that will be housed in the gallery, Suhanya Raffel will straddle east and west as Communist China clashes with the open and international environment that fostered Hong Kong’s art scene. It is a mighty challenge; opening a big cultural institution that sits atop one of the world’s most active geopolitical fault lines.

“In terms of censorship, we have not faced that in Hong Kong,” Raffel says, elaborating on the point about the risks of it being imposed. “Journalists often ask about that in our part of the world, but censorship is also something Australia has seen,” she says, referring to Andres Serrano’s controversial Piss Christ photograph that was vandalised while on display in Melbourne’s National Gallery of Victoria in 1997.

“Change is inevitable anywhere, you just have to look at what is happening in the US with museums and Black Lives Matter and the insistence and the recognition of diversity that flows right into the museum world as well. This is part of our lived experience. Every one of us, no matter what city you live in.”

As for Sigg, he was unavailable for an interview ahead of our print deadline and has mostly kept away from questions of what Beijing’s crackdown in Hong Kong means for his collection. Last year, in an interview with the Financial Times, he cited a statement from M+ promising that it will uphold and encourage freedom of artistic expression. “It confronts me to a degree,” he said of that promise, “but how will it play out over the years? No one knows.”

In Hong Kong, a city that has best been known as a place for making money, it is the commercial contours of the art world that are in sharpest relief. Art is not new to Hong Kong. Schoolteacher Dorothy Swan oversaw the first gallery, which opened on Chatham Road in the 1960s, providing artists with an exhibition space beyond City Hall. Big dealers such as White Cube arrived well before 2013. But it was the launch of Art Basel that year that transformed Hong Kong’s visual arts scene.

The collectors and the money arrived from around the world; lavish parties were hosted in high-rises and on the harbour of the former British territory. Hong Kong’s share of global auction sales soared. Underpinned by huge amounts of money flowing out of mainland China, which had its own booming contemporary art scene, Art Basel easily eclipsed anything else on the Asian art calendar.

Last year’s Art Basel, due to occur in March, was cancelled due to coronavirus. But perhaps the virus was simply the last straw following months of protests that tore the city in two. Usually peaceful streets were transformed into war zones during the second half of 2019 as police used tear gas and rubber bullets against protesters. In June last year, China introduced draconian national security laws aimed at stamping out any form of dissent or criticism of the Chinese Communist Party.

At the big end of town, gallery owners and auction houses say they are not concerned. Art market research firm ArtTactic says Hong Kong overtook London as the second-biggest contemporary art auction market in the world after New York last year with $US314.6 million in sales in the first eight months.

Tim Etchells is the co-founder of Art HK together with MCH Group, a Swiss firm which runs Art Basel. In 2013, MCH bought him out to create Art Basel Hong Kong, which together with sister events in Switzerland and Miami set the pulse for the global market in contemporary art. Etchells has mixed views on Hong Kong’s future as a regional art hub; fresh competition from other parts of Asia could be as much of a threat as Chinese censorship.

“Hong Kong will always remain as a prominent player in the region. But things are much more spread across Asia now. It is not just around what is happening in China,” Etchells tells AFR Magazine from France where he was riding out the second wave of the pandemic. He points to Taiwan, which has had a big art fair for the past three years, and to South Korea, which has a strong emerging collector base.

“With people’s uncertainty about leaving money in Hong Kong, there has been a shift in people moving investments into Singapore. We have seen a number of new galleries pop up in Singapore.”

When Etchells launched his first art fair in Hong Kong in 2008, there were 35 galleries compared with more than 100 today. He expects many of them to stay because of their commitment to the city. The preservation of Hong Kong’s favourable tax environment for importing art is essential to the city’s success.

Hong Kong does not levy any import or export duties on artwork. There are also no local sales, capital gains or value-added taxes. So far, there are no suggestions that will change. But things will change, Etchells says, if too many expatriates leave.

“I get a sense that the expat community, many of them who have been there a long time, are very nervous and many of them are leaving. COVID-19 has encouraged that a little bit. There are concerns about the government in China. But those that know it really well, they say China has always had an involvement in Hong Kong. It’s just a bit more prominent now than it was previously.”

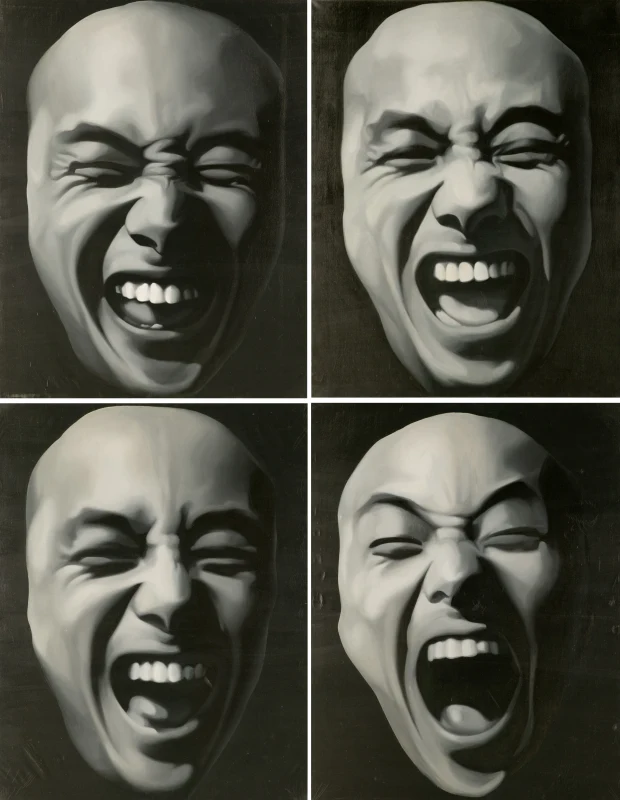

Wong Wing Tong, a 37-year-old Hong Kong painter, sculptor and performance artist, works from the Cattle Depot Artist Village in Kowloon’s To Kwa Wan district. Wong’s best-known pieces are his oil and mural paintings, which can take months to create without much outside interaction.

Wong says the national security laws have left a question mark over what artists are “allowed” to create. “We are still not very clear how this national security law will work,” he says. “We don’t know if we will be arrested for doing such and such. Our concern now is how different groups of people in the community will respond.”

For now, the main concern for artists is Hong Kong government funding under the new laws. In the past, artists could apply for grants by filling out a form, but Wong says their work is now vetted first by government officers who are likely to be paranoid about any subject matter that might offend Beijing. “Recently we have seen government officers coming down [to the village] to check. It didn’t happen so much previously. In the past, the village has been a free space without a lot of regulation. That is changing.”

Clara Cheung, a Hong Kong district councillor who represents the arts sector, says since the middle of last year, the Hong Kong government’s Home Affairs department has been tightening the criteria for councils to apply for arts funding.

“There is this feeling of the white terror arriving. There are a lot of extra questions and extra administration work for applicants applying for these funds now, even when a community project may not be political at all. The government is trying to control things as much as possible.”

Cheung also says artists renting a space in the To Kwa Wan village have to send in their portfolio instead of filling in a form as they used to do. It is a small, but potentially significant change in how art is made in Hong Kong.

Will that affect how the world sees M+ when it opens this year? Can the ambitious gallery rival those in western capitals if the surrounding atmosphere is one where artists are not free to provoke and critique? When Ai Weiwei was asked in July last year about the impact of Beijing’s crackdown on the future of the M+ he replied: “An art institution requires a liberty and a so-called freedom, and if that disappears, it will suffer like in the wintertime.”

For Raffel, this year will be the culmination of years of hard work. The protests and accompanying tensions have been challenging, but she loves working in Hong Kong. “It keeps me on my toes, one is never bored,” she says. “I really couldn’t imagine being anywhere else.”

And although the coronavirus has resulted in further delays, Raffel is grateful M+ did not open in the middle of the pandemic. This, she believes, is Asia’s time to claim its rightful place in the global art scene. “The public institutions are an important part of that storytelling and remembering. It is in these institutions that we see who we are. We will be putting Hong Kong on the global map.”

Michael Smith, the Financial Review’s China correspondent, was among the last Australian journalists working there until being forced to leave Shanghai in September.