This Group Is Helping Museum Workers in Ukraine

Written by Lisa Korneichuk. Originally published by Hyperallergic, 24 March 2022.

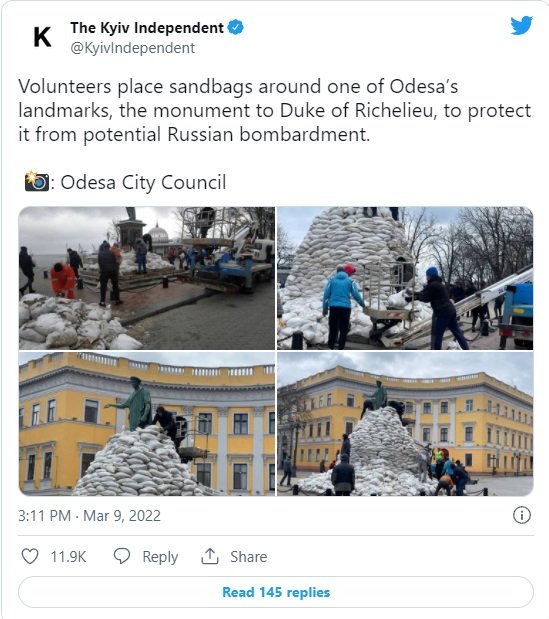

Many art and cultural monuments in Ukraine fall victim to Russia’s full-scale invasion along with civilians. Over the first 20 days of the war, Russian troops damaged libraries, churches, and a mosque, and shelled local historical museums in Chernihiv, Okhtyrka, Ivankiv, an art museum, architectural monuments in Kharkiv, and many more. As of this writing, they dropped a 500-kilo bomb on the Donetsk Regional Drama Theatre in Mariupol, where over a thousand people were hiding from the shelling.

While the Ukrainian governmental institutions are focused on saving the national art collections, local heritage and contemporary art remain vulnerable to the war threat. Moreover, museum teams in the regions often risk their lives staying in the war zones to guard exhibits. To save overlooked Ukrainian heritage from vanishing, local citizens, cultural workers, and NGOs organize independent initiatives and evacuate art that has fewer chances to survive the war.

On March 3, Olha Honchar, director of Lviv museum “The Territory of Terror” asked on Facebook if there were any funds supporting Ukrainian artists and museums in wartime. She later updated her post: “Meanwhile, we start making such a fund ourselves.” In partnership with the team of the NGO Insha Osvita, Olha launched Museum Crisis Center, a grassroots initiative aimed at helping museum workers in the emergency regions and evacuating artworks. The next day, first donations were made to the newly established fund.

The main task of the center was the rapid financial and organizational support of museum workers, many of whom found themselves face to face with the war and without a means to support themselves. The center has to look for ways to get around long bureaucratic processes to aid those who need it immediately.

Hyperallergic spoke to the Museum Crisis Center co-founders Olha Honchar and Alyona Karavai over Zoom about the balance between legal requirements and efficiency in times of war and their critical stances on international humanitarian institutions. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Hyperallergic: Tell us exactly what your organization is doing?

Olha Honchar: We have offices in Ivano-Frankivsk and Lviv [cities in the west of Ukraine]. We joined our efforts and found more people to launch the Museum Crisis Center or the Museum Emergency. I coordinate quick support for museum workers in war-torn areas that are under attack. We provide donations for basic things, like food, water, medicine. Many museum workers haven’t received salaries, their expenses increased. Our goal is to ensure that these people can survive the war, [save teams that] will rebuild the destroyed museums. So our routine is to monitor needs, obtain funds, make humanitarian transfers.

Together with the NGO “Insha Osvita,” we are developing an efficient algorithm for our work because within the bureaucratic Ukrainian system, it’s quite difficult to respond to people’s needs quickly. Everything is designed for a long bureaucracy. But in many regions we are working with there are no accountants, the treasury is bombed, or the culture department is not operating. Therefore, the only way to help is to send money directly on a personal card. Our task is to make it transparent and convince donors that help is received by those who need it.

The next step will be the reconstruction of museums and infrastructure, but these are large-scale things. At the moment it is crucial to support teams and people so that there is someone to do the reconstruction later.

H: You are also involved in the evacuation of works, focusing on grassroots initiatives and art projects that will be the last to come to the attention of government agencies for cultural heritage.

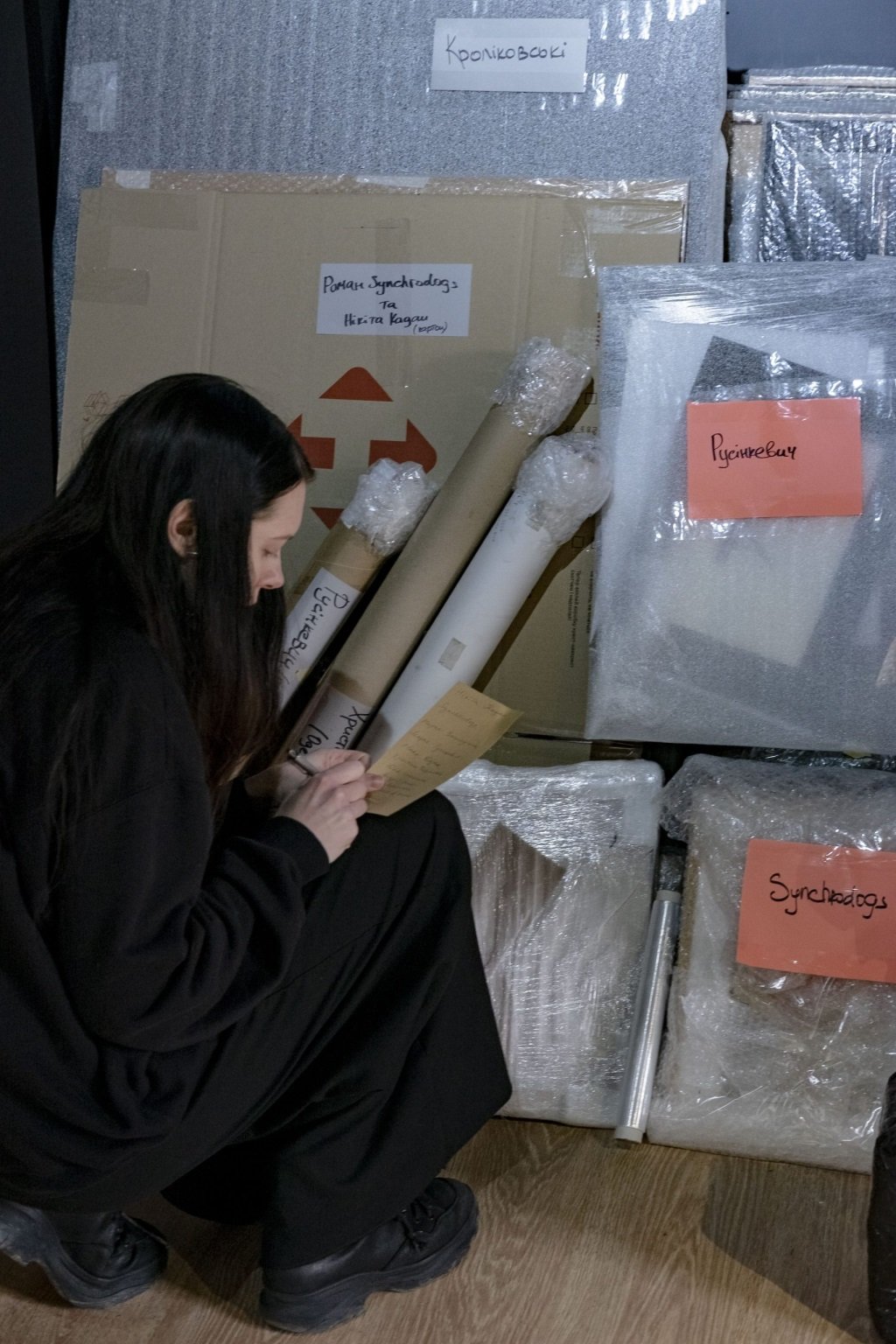

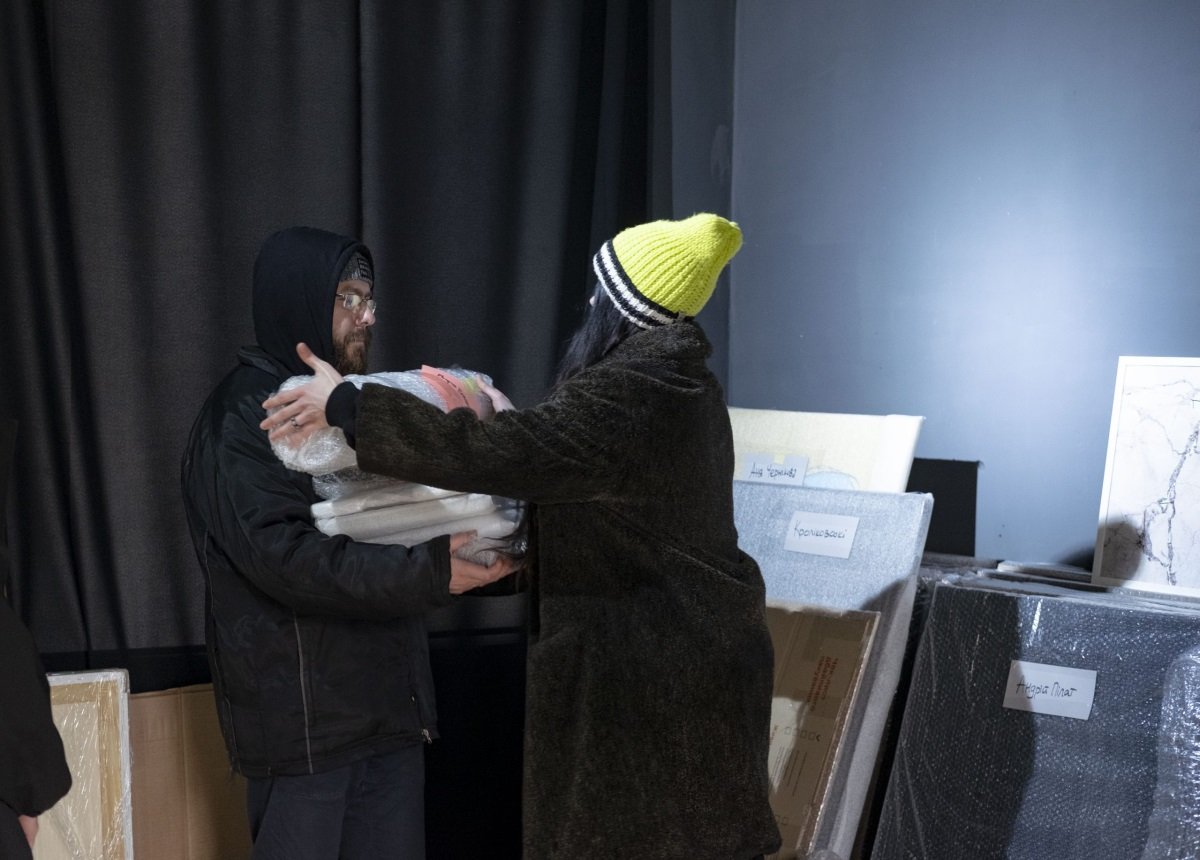

Alyona Karavai: Or won’t come at all. The other day we met with the Minister of Culture and they said that they were focused on objects that are defined as being ‘of cultural value’ under Ukrainian law, i.e. objects that are 50 years old and older. Their primary mission is to save large national collections. Thus, they are unable to help even the small state museums which they have under their control. Grassroots initiatives and contemporary art are generally beyond their sphere of influence. We [NGO “Insha Osvita”] evacuate works from artists’ studios, private collections, and art centers.

H: How often are you asked for help and do you carry out any selection of works?

AK: There is no selection. We help everyone we can. We’ve received 17 requests for assistance, so far we’ve fulfilled six. One request was from Mariupol, but it was clear that we could no longer help there. There are areas where we are powerless. We try to look at a specific situation, whether it is in our reach or beyond our capacity.

H: Do you work with platforms only or artists who want to save their oeuvre can request your help?

AK: Anyone can. So far we have more artists’ requests. We do not name those who we are evacuating, but there are well-known platforms in Ukraine that have approached us.

OH: We help museums that we have personal contacts with. Our monitoring team includes museum workers [and] directors of centers, who call each other and gather information about needs. It is very important for us to do this through proven contacts because now there are many suspicious situations, fake news. People are afraid to say what they have in museum collections because it is unclear for what purpose this information can be gathered. That’s why we rely on the trusted network and work through the close contacts I have made during my career, including as the director of the “Territory of Terror.” Simultaneously, other emergency teams are deployed on the basis of institutions and cultural communities. There is so much heritage that everyone has enough. Our focus is on regional small museums, which are close to us.

H: How do you evacuate artworks?

AK: We have a few volunteers on the ground. There are some people in Kyiv, in Odesa who help to evacuate artworks by buses. We’ve been looking for trucks. It takes a while to find any, we are not a transport company, we have never done that before. There were moments when we found a car and then it dropped at the last minute. The situation on the roads is changing fast. So if we were able to use a route yesterday, it does not mean that we can go there tomorrow.

H: How many works have you evacuated so far?

AK: [Over 400 works] have been secured into storage already. Well, we are just a transshipment point, we pass the works further to storage [hubs].

H: Do you receive any help from the Ministry of Culture of Ukraine?

AK: They can’t help us, but we communicate with them. I rushed to meet the minister, so they know about us, they saw our press release, we have a joint chat where we discuss what we do. But they do not provide us with resources, and we do not expect them to. Their task is to save large collections now. We are looking for help from outside.

H: You emphasize that you do not collect donations from private individuals in Ukraine. What are your sources of funding?

AK: They are external. […] We received offers from private patrons and organizations like UNESCO who will help. We understand that there are resources abroad, so we do not want to deplete our already small resources in Ukraine.

H: Could you as an NGO evacuate a collection of a state museum?

AK: No, we can’t. Legally [we have no right] to do so. There are also restrictions on what can be taken out of Ukraine, what can be accepted by the EU not to be considered as theft of cultural values.

H: What are the biggest risks and dangers to artistic heritage right now? What are the hottest spots right now?

OH: We were at a UNESCO meeting today, where everyone said that they did not believe that Russia had accidentally shelled our museums, archives, and churches. This [looks like] the deliberate destruction of Ukrainian culture. These actions align with Putin’s words that Ukraine has no right to exist. The directors of the archives spoke about the attacks on the archives, which contain evidence and historical documents about Russia’s repressions against Ukraine. [Their goal] is to erase our culture to zero and impose ‘Pax Russica.’ We told UNESCO that all the war rules, conventions, regulations, bans on attacks on civilians, medics, the press, museums do not work [here]. We shouldn’t compare this war with the Second World War, because it is a new form of evil that is now unfolding in our country. The rest of the world is not safe either. All the rules have been broken, so we must invent a new plan for how to survive this war and how to revive the lost [heritage].

Ukrainian culture can tell a lot about how to resist evil, to resist the totalitarian regime, in particular, to resist Russia. The new world is being born before our eyes. And it shows that the bureaucracy has screwed up. On all fronts. Now organizations like ours, at the NGO level, can be more effective than existing international funds initially conceived for these specific needs. We are now inventing new rules of the game. New leaders need to emerge in culture because the old world is no longer working.

AK: [In this war] … money can’t solve anything. Evacuating art or supporting museums is not about money, it’s about human resources and horizontal connections, power of civil society when there are people who care and who are willing to help.

H: What narratives about Ukraine have now appeared in the international media and which ones do you think should be emphasized and understood?

AK: Now everyone unites around the idea that Russia should get off of us, that no one [in Ukraine] wants to surrender. People want self-determination, therefore manifest the agency of Ukraine. I like the fact that more and more cultural figures are saying that Russian modern culture should be viewed through the lens of postcolonialism. Our problems do not occur by themselves, it’s not that we [Russian neighboring countries] are all suicidal around Russia, but it is Russia [who acts aggressively]. I’m not sure if this time we convinced the world community, but at least it is said more explicitly now.

OH: I hope the conclusion from this situation for us will be the understanding that we shouldn’t cut cultural projects. Culture should be a strategic direction [for Ukraine] on a par with defense. The insecurity of museums now, during the war, did not arise because museums did not want to repair windows or pack exhibits, but because there was no money. Museum workers are now as vulnerable as possible. We have to change that. Russia delivered a completely different level of state support for culture. We need to understand that [politics and culture] are connected, and this war must lead to changes in the cultural sphere.

H: How can people in the United States help Ukrainian art and culture right now?

AK: First of all, I would like to encourage you to get acquainted with Ukraine and reflect [on the ongoing situation]. Now is the time to pay attention to our artists and culture, to understand what we are talking about, why Ukrainian artists now refuse to even sit with Russian colleagues at panels and discussions. Donations are important, but paying attention to these issues and listening to us are of the same importance.

Among the foundations, I would recommend following the Ukrainian Emergency Fund, which supports Ukrainian artists. If there is the sentiment towards local museums in small towns and villages, you can contact us, knowing that this money will reach museum workers without long bureaucratic delays. We have been thinking a lot recently about the impotence and futility of such major international institutions like the OSCE, the Red Cross, and the United Nations. Their budgets for Ukraine are very large, but they have little direct impact and efficiency. It makes a lot more sense to donate to local organizations.

OH: During these days, and since March 3, we have supported 137 people and 30 institutions in 8 regions spending more than 5,000 euros. This is a small sum of money, but all of it was invested into direct support. In most cases, [Ukrainian] institutions cannot [legally] accept this money because the law does not allow such payments [for state museums], especially when it comes to money from abroad. We act as a mediator for these payments, so there are more and more requests.

AK: [The war has shown that] we need to work on museum reform. Well-known Ukrainian institutions turn to us because they cannot legally accept money from abroad. People are ready to donate, but such transactions are forbidden. Foreign partners should have a way to support museums like the one in Ivankiv without such intermediary companies as us.