The War in Ukraine Has Seeped Into Venice’s Glamorous Art Biennale

Written by James Tarmy. Originally published by Bloomberg, 20 April 2022.

Less than an hour after VIPs filed into Venice’s Giardini to view the opening of Venice’s 59th Art Biennale, a lone man in a dark overcoat unfurled a sign in front of an empty building normally used by Russia to show art. The sign read, in part: “I AM STANDING HERE IN FRONT OF THE RUSSIAN PAVILION AGAINST THE WAR AND AGAINST RUSSIAN GOVERNMENT CULTURAL TIES.”

He was quickly surrounded by a phalanx of Italian policemen who blocked the sign and then had him roll it up. A representative from the Biennale’s press office did not immediately respond to calls or emails requesting comment.

Speaking over the shoulders of the police officers, the man identified himself as Vadim Zakharov, a Russian artist who showed his work in the pavilion in 2013. “I think at least, people should be thinking about what they’re doing now, when Russians are bombing women and kids,” he said. “Propaganda may be more dangerous than bombs. Bombs kill some people, but propaganda kills millions.”

After answering questions from reporters, Zakharov, who now lives in Berlin, walked into the crowd. An hour later, looking slightly dazed, he bumps into one of the journalists and gestured dismissively at the throngs of expensively dressed people wandering through the Venetian garden. “Nobody wants to think about bad things,” he says.

A Long Lead

The international exhibition, which was delayed a year because of Covid, will officially open to the public on April 23 and run through Nov. 27. During that time, 80 national pavilions, some sprinkled through the city and others set in gracious, architecturally distinct pavilions within the Giardini grounds, will hold art exhibits.

In addition, a colossal, curated exhibition will be split between a space inside the Giardini parklands and the nearby, massive former shipbuilding warehouse known as the Arsenale. For this Biennale edition, that show, titled The Milk of Dreams and curated by Cecilia Alemani, includes work from more than 200 artists from 58 countries. On top of all that, a mixture of foundations, museums, galleries, and even some private individuals will put forth dozens—perhaps hundreds—of additional shows across Venice. (The most spectacular is an exhibit of absolutely massive panels installed by the German artist Anselm Kiefer in the Doge’s Palace, which has quickly become the week’s must-see show.)

This is, in other words, a massive undertaking, one that takes years of planning, organization, and preparation. And it’s freighted with meaning beyond just the art world: these are pavilions designed, historically, to telegraph soft power.

Given that lead time, it’s not—or at least, shouldn’t be—particularly nimble.

Yet, once the two artists slated to exhibit in the Russian Federation Pavilion backed out in protest in late February—“there is no place for art when civilians are dying under the fire of missiles,” wrote Kirill Savchenkov in an Instagram post—it became clear that this Biennale would be different than its predecessors. And while the overt nationalism of the last Bienniale presaged Putin’s war, until previews this week, what wasn’t clear was how different it would be.

Last-Minute Changes

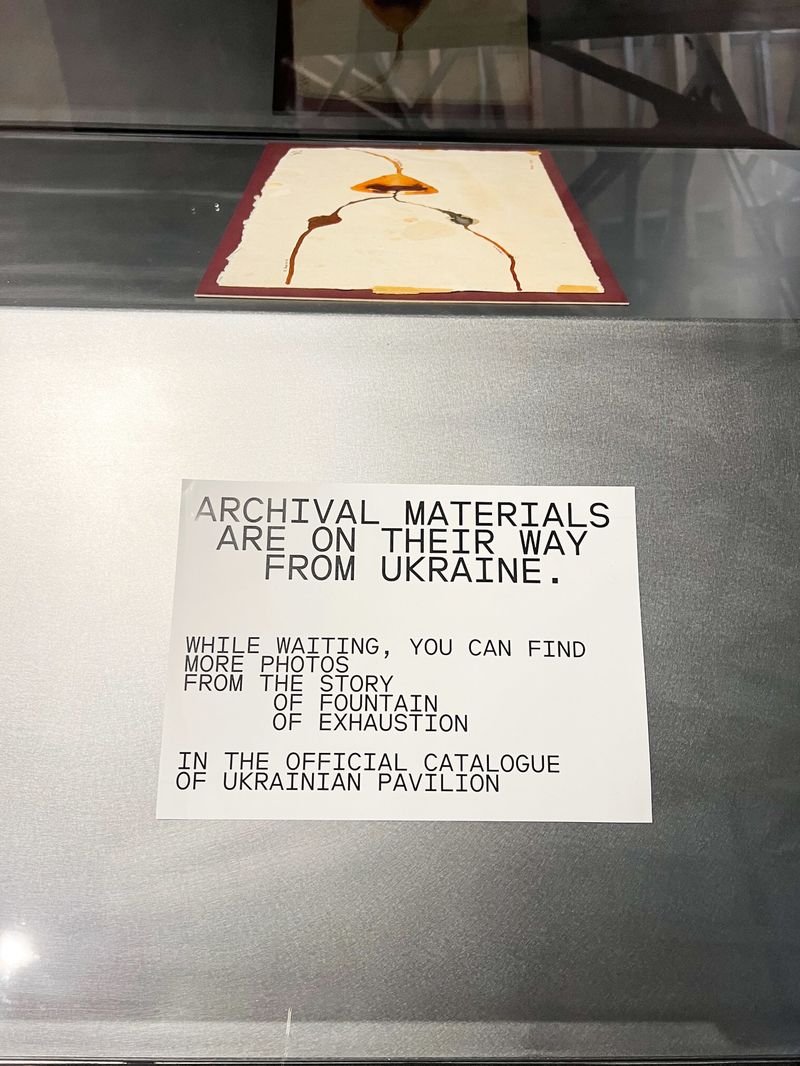

Some of the changes are explicit, such as a last-minute installation by Ukrainian artists in the Giardini featuring a tower of sandbags reminiscent of those used to protect national monuments.

Others are more subtle. For instance, in The Milk of Dreams, wall text for an artwork by the Ukrainian artist Maria Prymachenko notes that while she “faced the horrors of the Second World War and, eventually, witnessed the Chernobyl nuclear disaster,” the gravest threat to her art “dates to last February when, during the Russian invasion of Ukraine, many of her works risked being lost forever in the bombing of the Ivankiv Museum, in which they were stored.”

The war has also seeped into exhibitions that weren’t explicitly designed to take it into account, creating opaque, albeit effective, moments. Take a piece by the artist Tomo Savić-Gecan, who represents this year’s Croatian Pavilion and who designed a work that became infused with unlikely pathos when Russia began its invasion.

Savić-Gecan chose not to use a physical space; instead, he spent a year and a half developing an algorithm that would pull a news headline from one of 250 sources every day. The program then feeds the headline to five performers with earpieces, telling them where they should perform that day, what their movements should be, and how long they should perform. (Most performances will take place inside other national pavilions, so the performers won’t have to spend seven months sprinting back and forth across Venice and its canals.)

Given that the Russian invasion currently dominates front pages around the world, Wednesday’s prompt, chosen randomly from Italy’s La Repubblica was, unsurprisingly, about “brutal attacks” in Mariupol, Ukraine’s most battered city. Performers entered the Finnish Pavilion unannounced, and almost imperceptibly began a series of subtle, choreographed steps that could only occasionally be distinguished from the movements of other visitors. This was nothing as literal as acting out a bombing, but—taken as a response to an unfolding atrocity—the work was surprisingly moving.

But the headline could have easily been about something more banal. “I have a lot of problems with the kind of ‘look’ of solidarity that is so prevalent,” says Elena Filipovic, the director and curator of Kunsthalle Basel in Switzerland and the curator of this year’s Croatian Pavilion, referencing the fact that at the same time Russia invaded Ukraine, the U.S. started bombing again in Syria. “But everyone was only talking about one war and not the other.”

Reminding viewers of how and why they’re fed information, she continues, is exactly the point of Savić-Gecan’s artwork. “I don’t know that art can stop a war, but art can make us talk about all the things that we can control in the world, and the things we should be doing to be better informed,” she says.

Making an Impact

Some events surrounding the Biennale are intended for a more direct, tangible impact to help Ukrainian artists, civilians, and cultural institutions.

Notably, the art collector Francesca Thyssen-Bornemisza’s TBA21 foundation has banded together with Brant Foundation and Therme Art to organize a last-minute auction in support of Ukraine. Proceeds will go to a range of charities, from 100% Life, which supports Ukrainians living with HIV, to the Ukrainian Emergency Art Fund, which provides financial aid to Ukraine’s cultural workers.

“This fundraiser was basically put together in the last two weeks,” says Thyssen-Bornemisza. “I reached out to all the artists in my collection and asked them to donate works, and Peter Brant did the same.” Artists with work in the auction include market stars David Salle, Richard Prince, and Josh Smith. Organizers decline to give an estimate for what the auction might raise, but sales of the 59 pieces in the auction could easily exceed $1 million.

The website for the fundraiser, which will be held in Venice’s ornate Scuola Grande Di San Rocco on Thursday, just went live on Wednesday morning. “This is something that will be very, very successful,” Thyssen-Bornemisza continues. “I’m sure it will be, because everyone’s heart is in it.”

In the meantime, the whirl of openings, concerts, dinners, parties, unveilings, and performances will continue in Venice for the week.

Zakharov, the artist who protested, is likely to miss them: He plans to stay in the city for only two days. “The west still thinks that after a few months this will be done,” he says with a shrug. “It’s so naive.”