Greening the gallery: How London’s arts institutions are responding to the climate emergency

Written by Nancy Durrant, published originally by Evening Standard, 4 November 2021.

As world leaders drift (or fly) away from COP26, it’s clearer than ever that every individual and organisation needs to buck up their ideas to mitigate the climate emergency right now, London’s cultural institutions among them. Those which receive public funding were already under pressure to make significant changes - environmental responsibility is now one of the four Investment Principles (things you have to prove you are actively working on in order to be given any money) in the Arts Council’s ten-year strategy Let’s Create, brought in last year. But, it turns out, they and many others have been changing already for some time, without this kick up the backside. But how?

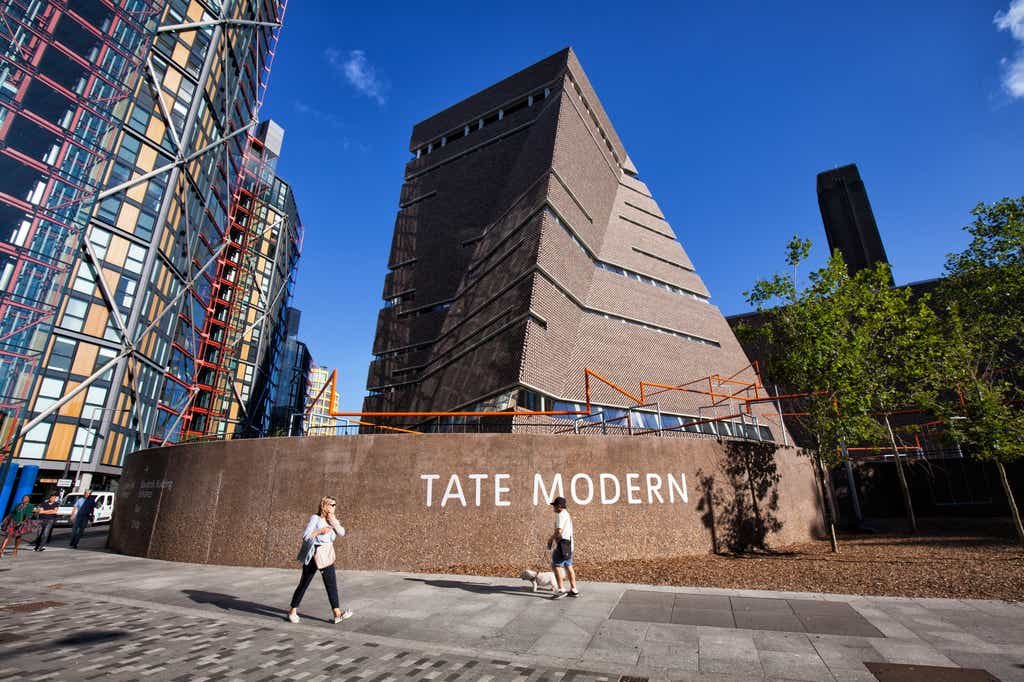

The first area to look at is, of course, the buildings. Tate Modern, says director Frances Morris, recognised the climate emergency “as early as 2007, so a lot of thinking went into the Blavatnik building, about how to challenge then-conventions around new buildings.” The ‘twisty one which isn’t the Turbine Hall’ has large, visible solar panels, and only sustains museum conditions within the galleries - the public areas are not heated. Rainwater flushes the loos across the Tate Modern complex.

The British Museum’s Archaeological Research Collection, a new storage and research facility in Wokingham, also “demonstrates how new technology and sustainability can be an active part of the future of museums”, says the BM’s director, Hartwig Fischer. It is all-electric, and landscaping elements such as swales to manage water run-off from roofing areas have been created which, when planted, will create new habitats to increase local biodiversity.

But not everyone can build new. One of the biggest problems for London institutions is that most of their buildings are both very old (and therefore not exactly high-performance in any but the most temperate drizzle) and listed to the hilt. “Even if you are using green energy, if you have a building where the roof is just kind of held together with string, you’re just pumping more energy to it,” says Philippa Simpson, the V&A’s director of design, estate and public programme. So getting things sequenced correctly, when you do capital or large-scale maintenance works, is super-important. The Royal Academy used the renovation of the RA Schools in 2018 to adapt the buildings as far as possible, earning them a BREEAM certification, which assesses sustainability. “We’ve done our best within the possibilities of a historic, Grade One listed building,” says Axel Rüger, the RA’s secretary and CEO.

Organisations are a lot more than just their buildings though - changes can and are being made not just in the places themselves, but among their people and their programmes. More than once the people I speak to for this piece describe the changes as “granular” - small things that can have a cumulative effect over time. The V&A now encourages its staff to use tablets instead of printouts in meetings, for example, while it, Tate Modern, the National Theatre and the Lyric Hammersmith are among the institutions to set up beehives on their property.

Many institutions have followed the Old Vic’s early example of phasing out paper tickets in favour of showing them on a phone or printing at home, while all those I speak to mention that single-use plastic has been all-but eradicated (though as Eleanor Lang, the executive director of Theatre Royal Stratford East, points out, since the pandemic the need for lateral flow tests, disposable masks, aprons and gloves for food and beverage handling has unavoidably marred their copybook on that front).

One of the biggest areas of behavioural change is travel. Since even before the pandemic, many at London’s cultural institutions are questioning how often it’s necessary to attend conferences abroad when you can do so remotely, but even more significant, says Simpson, is “travel with [museum] objects. Covid, in a slightly dark way, has helped with this because we’ve all learned to do things more efficiently, virtually. So for example, when we’re sending loans abroad, rather than travel with them on a plane, we can oversee [delivery and installation] with video calls - we can direct what’s happening [to items from] our collection through a phone or tablet.” Tate does the same thing, while reducing flights overall by around 40 per cent, says Morris, and the Natural History Museum has banned domestic flights and all taxis, and encourages staff to walk or cycle where possible.

Exhibitions, of course, pose their own unique issues when it comes to sustainability. The RA now asks that materials are recycled or recyclable and ask external contractors what their policies are in terms of waste management and recycling; Simpson says the V&A does everything it can to reuse materials at the end of a show - some material from temporary exhibitions in the South Kensington building is being repurposed in the build of the soon to be revamped Young V&A in Bethnal Green.

Loan exhibitions “always necessitate transport,” Rüger says, but “where we do hope we can make a difference is for example in packing materials. We use a lot of packing materials that are being reused or [object] cases that are a bit like suitcases where you can fit them out internally so that the work fits perfectly, but they are standard cases on the outside, being constantly reused. In the old days, crates were being built specifically for works when they travelled and then destroyed once the trip was completed and that is obviously not sustainable.”

There are still major challenges. The targets many organisations have set for themselves are daunting. In April, the Science Museum committed to reaching net zero by 2033, covering both the carbon footprint of their own operations, and crucially, their supply chain, which is, says deputy director Julia Knights, “about 94 per cent of our whole carbon footprint”. That will be a drastic cut of carbon emissions across five museums and collection sites - “everything we buy, everything we sell, everything we throw away, and the carbon footprint of our exhibitions and galleries, is now calculated.”

And there’s only so far an organisation can go on its own. Waste management is a struggle, says Rüger. “We recycle on site and separate and so forth. But then it has everything to do with the capacity in Great Britain, in terms of plants, to recycle the materials and I think they say it’s only about five per cent of what’s generated in refuse that is actually being put through recycling, which is somewhat dispiriting.”

Then there’s the vexed question of money. The Science Museum just announced a major new climate change gallery, Energy Revolution, sponsored by Adani Green Energy, one of India’s biggest renewables companies. And yet, that company is a subsidiary of the Adani Group, a multinational involved in coal extraction (a protest against their involvement took place at the museum last week, and two of the museum’s board members resigned as a direct result of the Adani deal). Critics argue there’s a disconnect between the museum’s rhetoric and listed actions, and its stated stance on accepting money from companies that trade in fossil fuels. In 2019 director Sir Ian Blatchford sent a lengthy email to staff (on which Knight demurs from commenting further) acknowledging the “challenges and ethics” of climate change, but asserting that oil and gas companies “have the capital, geography, people and logistics to find the solutions [to climate change] and demonising them is seriously unproductive”.

BP (also one of the British Museum’s longest-standing corporate supporters), Equinor and Shell are prominent sponsors for permanent and temporary exhibitions at the Science Museum, including the recently opened Our Future Planet, which directly deals with issues of environmental change and is sponsored in large part by Shell, which Blatchford defended by noting that “alongside reducing carbon emissions, carbon capture and storage can be one contribution in the fight against climate change."

Bill McGuire, a professor emeritus of geophysical and climate hazards at University College London, called this “both greenwash and hogwash,” telling the Art Newspaper “The only reason that fossil fuel companies are keen on link-ups such as this, is to give the impression that they are actually bothered by the climate emergency.”

Morris is bullish on this point. “Once you’ve dealt with your own place, you need to think about your relationships with other people. So we have built environmental credentials into an ethics committee for when they review all our partnerships. And that’s a really fundamental shift from 10 years ago, when BP was sponsoring us - it’s really seen as a moral obligation to take the stance. It also underpins our investments policy, so we need to make sure that our investments, our portfolio, is sustainable.”

“Support and funding is a constant tightrope walk,” Rüger says (the RA does not, as far as he is aware, have any funding streams that derive from fossil fuel companies). “But in principle, we all would like to only accept money from businesses that have the same principles and ideas as we as an organisation. It’s a huge challenge, because we also have to pay our bills. And, you know, often when people object to us taking money from certain sources - it doesn’t have to be environmentally related - there’s never really a good alternative mentioned. And that doesn’t make it right; it just illustrates how complicated it is for any arts organisation or indeed any charity.”

Still, London’s arts organisations take their responsibilities seriously, and many are aiming to bring visitors along too with new programming. In 2019 Tate declared a climate emergency, and recently held a weekend of events dedicated to environmental issues. The Natural History Museum is currently running a large-scale programme engaging the public in the question of humanity’s impact on biodiversity (spoiler: we’re terrible) and how we can mitigate it. Also imminent is a project the museum has been quietly working on for the last 11 years primarily aimed at policymakers, called the Biodiversity Trends Explorer, an online free portal which will for the first time make it possible to finely measure trends in biodiversity, country by country, going back to 2000. The idea is to assist with predictions, says the museum’s director Doug Gurr. “We think it will have a big impact in terms of the public policy debate.”

The Science Museum recently opened its Amazonia exhibition, a series of photographs by Sebastiao Salgado shedding light on the plight of indigenous groups living in the rapidly diminishing Amazon rainforest, and in January it launched a series of free, virtual Climate Talks from speakers from across the globe, such as representatives of small island states who stand to lose everything, former world leaders and scientists.

Then there’s advocacy within the sector - Lisa Burger, executive director and joint chief executive of the National Theatre, says that one of the most significant opportunities that the organisation has been afforded during the pandemic has been “to take a leading part in spearheading the Theatre Green Book. It’s a collective response across the whole of theatre, on how we can respond to the climate emergency and think in three models, how we can change the way we make productions, how we look at our buildings and how we look at our operations.”

The first volume of the book, which is still in its beta stage, sets standards for making productions sustainably, with baseline, intermediate and advanced levels demanding efforts ranging from making sure 50 per cent of materials come from reused or recycled sources, to stipulations about the level of sustainability demanded from contractors.

All in all, I find this encouraging. But is it enough? Simpson hopes so, but acknowledges that nobody can rest on their laurels. This is a huge task. “Every single thing and every single area that we work in has to change.”